Their third album, Toys In The Attic, had changed everything for Aerosmith in 1975, going Gold and rising to No. 11 in the Billboard chart. In 1976, with the follow-up, Rocks, the band would take things to yet another level.

While the Toys… album has subsequently outsold it two to one, notching up eight million sales thanks in a large part to it containing Sweet Emotion and Walk This Way, Rocks actually charted higher, peaking at No.3, and highlighted a year when the band had five hit singles.

With hindsight, the albums used the same template and play like twins. Rocks, though, is the lyrically darker and musically heavier. Its songs chronicle the band’s growing stature as a touring act as well as an unhealthy level of drug abuse.

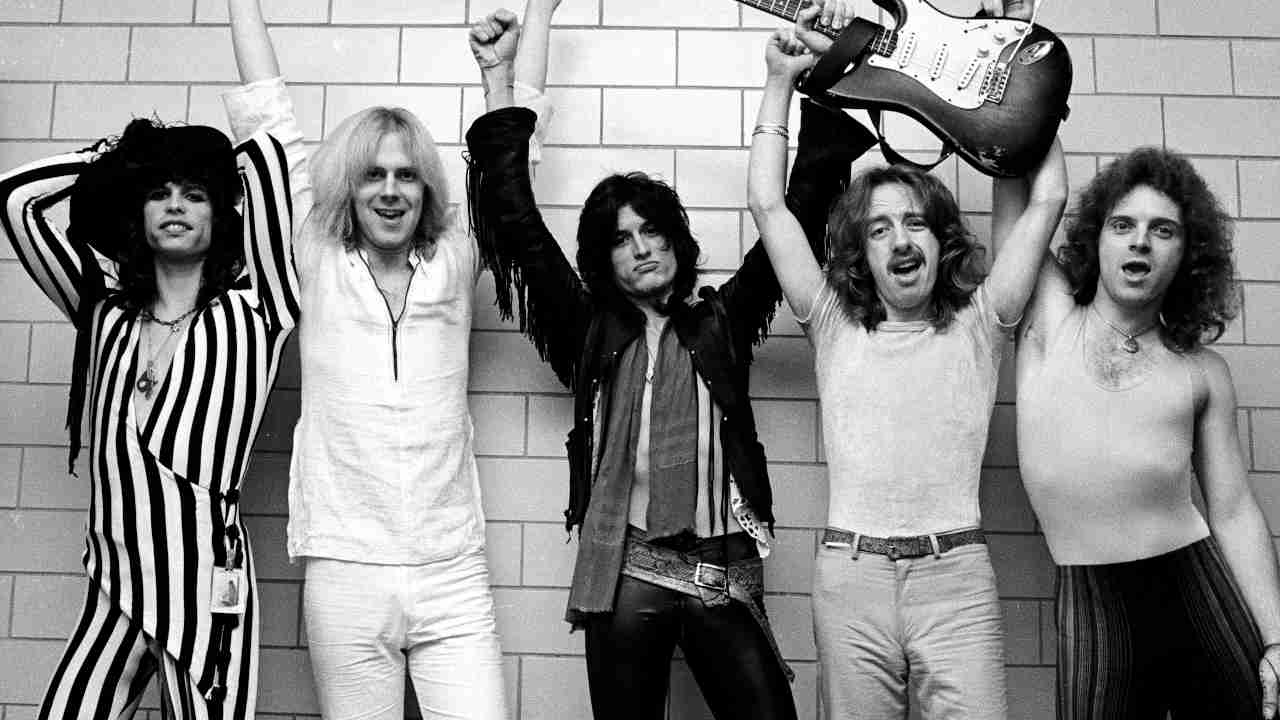

After years when critics regularly lambasted the Boston five-piece as the poor man’s Rolling Stones, influential US music magazines Rolling Stone and Creem finally began showering Aerosmith with compliments. The audiences (dubbed The Blue Army by the band due to the prevalence of denim in the arenas they were playing) grew exponentially and started behaving almost as outrageously as their heroes – boozing, popping pills and throwing firecrackers.

Aerosmith had always liked but to drink but, during the nine-month, 99-date Toys In The Attic tour (which never left the North American continent), cocaine was everywhere – thanks often to a crew who were as keen on it as the band.

“We drank a lot because of the blow and we got blown a lot because we drank a lot,” shrugged singer Steven Tyler. The backstage term “production meeting” was slang for going somewhere to do a load of lines. Come the sessions for Rocks, as their buddies The Faces had observed a year earlier, what were once vices were now habits.

Guitarist Joe Perry told me in 2014: “The main influence that the drugs will have had was that we were partying too much and didn’t notice the kind of money we were spending or take care of the decisions we were making – I don’t think we could have spent that much on drugs…”

They didn’t, of course, as Perry’s fellow guitarist Brad Whitford recalled.

“My back account started to grow and I felt very wealthy all of a sudden,” Whitford later said of the sudden upswing in the band’s income. “I wasn’t, but $10,000 felt like a million. I was 22. I thought, ‘Man, I can buy the kind of car I’ve always dreamed about. That’s when I got my first Porsche. I think that’s when we all got our first Porsches.”

On December 30, 1975, after the third of three shows at the 14,000-capacity San Diego Sports Arena, Aerosmith finally drew breath. At the suggestion of co-manager David Krebs of the band’s management company Leber-Krebs Inc, Columbia had re-released Dream On, the power ballad from their self-titled 1973 debut that had always been a hit with audiences on tour. Three years earlier it peaked at No.59 on the Billboard chart. This time, it sailed to No.6 following its release in January 1976.

Basking in this glory Aerosmith took January off and investigated their new “clubhouse”, purchased for them in the autumn of ’75 while they pinballed around North America. It was sourced for them by Ray Tabano, the guitarist who co-founded the band with Tyler and Perry before being replaced by Whitford in 1971. Since then, Tabano had run the fan club and done anything else management asked of him.

One such task was identifying premises that could serve the band as a lock-up, offices and rehearsal space. Up a cul-de-sac on an unassuming residential street in Waltham – a city suburb about 10 miles east of the band’s apartment in Beacon Street in the centre of Boston – Tabano found it.

Krebs checked over the empty corrugated-iron clad warehouse, designated 55 Pond Street, and agreed a $40,000 deal. That investment saw the upstairs space converted into a lounge and offices, from where Tabano ran the lucrative merchandising business, installation of some state-of-the-art wiring and the construction of a stage.

The band christened the building, big enough for them to park their flash new cars in, the Wherehouse. They hung drapes from the high ceiling to improve acoustics and ambience, and adorned the walls with heroes – a huge montage of Mick’n’Keef images, alongside Chuck Berry, Rod Stewart and more. When Aerosmith weren’t in residence, fellow Leber-Krebs outfits Ted Nugent and Mahogany Rush would also use the space. It also provided a launchpad for up-and-coming local band Boston – the future AOR superstars played a showcase there that got them their deal.

Aerosmith – Back In The Saddle (Live At The Summit, Houston, TX, June 25, 1977) – YouTube

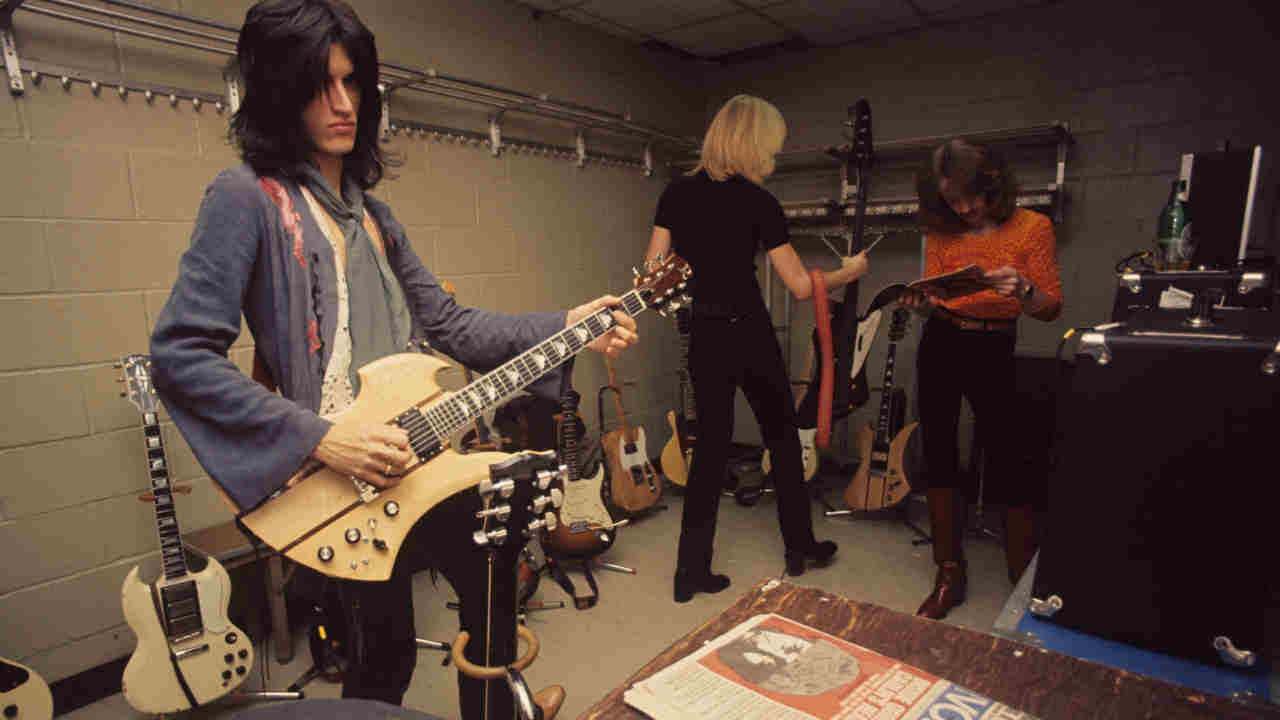

In February, the Record Plant’s mobile unit backed into the Wherehouse and when the door closed behind it, work on Rocks began in earnest. Jack Douglas – who had co-produced Aerosmith’s second album Get Your Wings and was at the helm for Toys In The Attic – unsurprisingly got the job again, although this time the band took a co-production credit.

Whitford explained why their working relationship with Douglas proved so fruitful. “The thing about Jack was he was there living with us in Boston, working, playing drums, a little pot/blow/beer,” said the guitarist “He‘d try anything, and it inspired us. He was a mad genius but so solid.”

Douglas was also a joker, as drummer Joey Kramer recalled: “Jack convinced me that if ate nothing but greens for two weeks I’d smell like a freshly cut lawn. This went great until I got really constipated, then Jack had me drink a quart of prune juice to push it all through. He hid a prototype sound-activated tape recorder in the bathroom. When he rewound the tape there was a full day of horrible gas and flushing toilets…”

Whitford: “When you’re in the studio with Jack you laugh, roar, do silly shit – it’s loose. I’d throw ideas back and forth with him and leave it up to Steven to come up with a great lick and a vocal.”

On Rocks the lyrics, almost exclusively written by Tyler, came last and usually infuriatingly late. All the band knew, though, that the singer made Aerosmith unique and that came at price. Bassist Tom Hamilton told me of his respect for the singer’s wide range of input.

Steven, musically, has so much knowledge,” said Hamilton. “Not schoolbook knowledge just built-in knowledge from growing up with his father being a classical pianist…”

Douglas, meanwhile, saw the strengths of the others and encouraged them to write. On Toys In The Attic that encouragement prompted Tom Hamilton to deliver Sweet Emotion and Uncle Salty, while Whitford chipped in with Round And Round. For Rocks the pair stepped up to the plate again.

In the Wherehouse, as the band tracked through February and into March, the character of the two guitarists was highlighted on their respective songs. Jack Douglas has subsequently described Joe Perry as a great improvisor; Whitford more a technician, methodical and dedicated – recording take after take if needed.

On Rocks the pair of them got to shine, although predictably, Perry’s contributions were the flashier. Joe conceived Rats In The Cellar as a counterpart to Toys In The Attic’s title-track, as he would later quip: “We were getting lower down and dirty. So the cellar seemed like a good place to go.”

Tyler’s lyrics were clearly about the influx and impact of drugs on Aerosmith: “Things were coming apart, sanity was scurrying south…” When he sang about “losing my connection” in the third line of the song he was referring to a dealer who supplied top-purity heroin to Perry – until the dealer was killed in nefarious circumstances.

In his 2014 autobiography Rocks: My Life In And Out Of Aerosmith, Perry paid the dealer some kind of complement when he recalled the genesis of Back In The Saddle.

“I was in my bedroom, flat on my back, fucked up on heroin, playing my six-string bass,” he recalled. “The music flew out of me – all the parts, all the riffs. It came in one special-delivery package. I was still in the stage when drugs were opening doors to my imagination…”

Two of Perry’s other songs – Lick And A Promise (about the band’s efforts at winning an audience) and Get The Lead Out (Tyler’s exhortation for them to get up and dance) – were both brutal and fast-paced, the products of a restless mind as well as his habit. “In some sense all these songs were about movement,” the guitarist later reflected.

Aerosmith – Rats In The Cellar (Live Texxas Jam ’78) – YouTube

His fifth, Combination, written alone, nails the band’s health and wealth in the lines: “Walkin’ on Gucci, wearin’ Yves Saint-Laurent, Barely stay on ’cause I’m so Goddamn gaunt.”

Whitford, meanwhile, conceived the funky Last Child – the album’s first and biggest selling single, complete with folk musician Paul Prestopino on banjo – and Nobody’s Fault. The latter starts with the sound of Perry and Whitford’s guitars playing odd chords loud and in-synch – Tyler’s idea as the song didn’t have an intro. Seventeen seconds in the vocal mic picks up the noise of a door opened by the union “engineer” Columbia Records insisted was present at all sessions – Tyler’s idea to leave it in as he doubted he’d better his take. That kind of loose flexibility was common.

Perry recalled Tom Hamilton writing Sick As A Dog on guitar, “so when we recorded it he played it on guitar with Brad. I’m in the control room playing bass listening to what I was doing. Then it needed a solo so I gave the bass to Steven and went back into the studio to play guitar. So the end is three guitars and Steven playing bass…”

Long before he ever wrote a finished lyric, Tyler’s fingerprints were over every song. Eventually they had an album almost complete, but relocated to Manhattan’s Record Plant studios to finish. There – as he had done on the previous three albums – Tyler came up with a piano-led power ballad, this one called Home Tonight. Better loved, though, was opener Back In The Saddle, the singer’s “nostalgic harkening to every Spaghetti Western I ever saw”.

It was a big production number full of sound effects: coconut shells as horses hooves; a whip effect produced by Tyler whirling a guitar chord overhead close to strategically placed mics; and multi-tracked foot-stomps for which he wore an old pair of boots he’d had in high school boosted by a tambourine gaffer-taped to them by David Johansen, who dropped by, the New York Dolls having befriended Aerosmith earlier in the year.

Rocks – a title Perry had originally proposed for Toys in The Attic – was released on in May 1976, after the band had already been touring the US for a month. Its black sleeve featured a band logo and five diamonds perched on a mirror, representing both the five members and the cocaine slang of the title. It pretty much set the tone for hedonism that would follow.

Tyler: “The stadiums we played were getting bigger. Backstage set-ups became more elaborate. When we performed at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, there were pinball machines and ridiculously slammin’ naked mannequins that lined the hallways from the stage to our dressing rooms…”

Back at the hotels, Tyler’s room was party central. “We threw the TVs out of the window into the pool,” he wrote in his autobiography, Does The Noise In My Head Bother You? “If you kept the extension chords on the TVs, when they hit the water they exploded like depth charges.”

The singer was arrested more times than he can remember. He was incarcerated in Memphis after “repeated profanities” on stage, in Lincoln, Nebraska for setting off firecrackers in a Holiday Inn, and in Germany with new girlfriend Bebe Buell for blowing hash in the face of a customs officer at the airport.

The whole touring party’s reliance on drugs made crossing international borders a high-risk enterprise. For Rocks, in addition to 74 dates in the States – including their first big outdoor headliner to 80,000 at Michigan’s Pontiac Stadium in June – they played 14 shows in Europe (four of those in the UK) and seven in Japan. But brushes with the law like the one in Germany meant that apart from two dates in 1977, including the Reading Festival, Aerosmith wouldn’t need a passport again until touring Pump in 1989. The album though, knew no barriers.

The last word goes to Joe Perry. “I have a theory that with any kind of art you go through phases, periods of creativity – then periods where you have to work at it,” he said. “Sometimes you just wake up and explode, others you have to make yourself do it. There’s an ebb and a flow – especially in a band where not everyone is going to be in the same place at the same time.

“In the ’70s, when we were learning how to be recording artists, Rocks was arguably the peak, when everybody was firing on all cylinders. We were in a really creative space and everybody was in that space at the same time. That’s why it worked.”