“I know it sounds like a joke musical but one of my ancestors was a pirate in the Caribbean. He looked a bit like I did when I was 21 in Roxy Music”: The amazing things Phil Manzanera discovered when he looked into his past

Best known for his work in Roxy Music, British-born guitarist Phil Manzanera’s fascinating life is captured in his recent memoir, Revolución To Roxy. Outside of Roxy, he’s released countless solo albums, created the ‘special occasion’ supergroup 801 and collaborated with his bandmates Andy Mackay and Brian Eno, as well as David Gilmour, John Wetton and Godley & Creme, to name but a few. He discusses his remarkable career so far and his box set 50 Years Of Music.

Phil Manzanera can’t get used to the fact he’s been recording music for more than half a century. “You blink and suddenly it’s 50 years,” Roxy Music’s guitar supremo tells Prog. “What happened? Where did it go? There’s not going to be another 50 years, so now it’s like, ‘I need time! There’s still stuff to do.’”

As our conversation unfolds, it becomes clear that, yes, the 73-year-old still has plenty to do. But we’re here to salute 50 Years Of Music, a hefty 11-disc box set that traces the arc of Manzanera’s solo career, from 1975’s Diamond Head to 2015’s The Sound Of Blue. A bonus disc of rarities, drawn from his own archive, helps expand the story further: a co-written Pink Floyd demo, a live Roxy Music gem, jamming with famous friends, and so on. The collection feels very much like a companion piece to his recent memoir, the highly absorbing Revolución To Roxy.

It’s certainly been an extraordinary journey. Born in post-war London to a Colombian mother and English father, Manzanera’s peripatetic childhood took him across the Americas, exposing him to a whole host of musical and cultural influences. He was back in London, attending Dulwich College, when he started his first significant band, prog rockers Quiet Sun. But his life took another turn after spotting a Melody Maker ad in late 1971: ‘Wanted: The perfect guitarist for avant-rock group: original, creative, adaptable, melodic, fast, slow, elegant, witty, scary, stable, tricky. Quality musicians only.”

This fledgling “avant-rock group” was, of course, Roxy Music. By early the following year, having flunked the first audition, Manzanera was in, replacing David O’List. His textural approach to guitar – using effects, distortion and unorthodox tunings – proved an ideal fit for Roxy’s art-school aesthetic, topped by a striking visual image of red silk jacket, white boots and diamanté-studded fly glasses. He quickly found himself in demand elsewhere too, appearing on albums by John Cale, Nico and a post-Roxy Eno in the first half of the 70s.

Diamond Head very much set the tone for his solo output – it’s a multi-handed effort featuring Eno, Robert Wyatt, ex-Matching Mole bassist Bill MacCormick, Quiet Sun’s Charles Hayward and others, reflecting the collaborative spirit of the entirety of 50 Years Of Music. The box set doesn’t even have room for Manzanera’s shared projects down the years, from albums recorded with John Wetton and Andy Mackay to Peruvian-Mexican singer Tania Libertad and, most recently, Tim Finn.

The defining thread that links all Manzanera’s work is a daring sense of adventure, a relish of happy accidents. “When you’re coming up with new stuff, you don’t know where it’s going,” he explains. “Then something suddenly appears out of nowhere and that’s such a morphine sort of rush. That’s when I’m at my happiest. Music has always helped me, from the beginning in Cuba right through to today. It’s been a constant throughout my whole life.”

What brought this box set on?

Basically, it’s been 50 years. I’ve collated my life stories in my memoir, Revolución To Roxy, and I’ve sort of done the same with my solo musical adventures, very imaginatively called 50 Years Of Music. I think that was all sparked by the 50th anniversary of Roxy two or three years back. I thought, “Hang on, I’ve got to get my skates on!”

Roxy seemed to combine so many things… I was thinking, ‘Wow, this is my dream!’

What is your very first musical memory?

I was born in ’51. When I was about five, before I went to Cuba, I’m watching The Lone Ranger and The Adventures Of Robin Hood and I’m listening to those songs: ‘Robin Hood, Robin Hood, riding through the glen…’ But the big change was going to Cuba when I was six. Everything was so exotic. All those people who became the Buena Vista Social Club were at their prime, playing in nightclubs that I was dragged along to. Exotic women would be dancing in incredible outfits, and there’d be singers like Omara Portuondo.

Then my mum gets a guitar and starts teaching me. Actually, it’s that one there [points to an acoustic in the corner of the room]. It’s with me every day. And those were classic South American and Mexican songs and boleros. The boleros were like the blues of South America. So I wasn’t listening to skiffle or learning from Bert Weedon’s Play In A Day. It was a different cultural experience for me.

Was it inevitable that you would become a musician?

It wasn’t inevitable, but things moved apace. We left Cuba after the Revolution and moved to Hawaii, where there were hula dancers and great Hawaiian guitar. Then, in Venezuela, we watched the Elvis films. When I was at school there, these American college kids would come over and play covers of Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry. And I was listening to London on my dad’s shortwave radio.

So I was fascinated by a combination of the exotic and rock’n’roll, all fuelling this thing. It wasn’t that I wanted to be a professional musician; I just wanted to play the guitar. Then I said, “Send me to school in England.” And they did, aged nine. I learned so much from those guys at Dulwich College. It was a public school, but 90 per cent of people were there for free, paid for by their local councils. All different people. A lot of them were from Beckenham: “We saw this guy called David Bowie at the Three Tuns last night!” So you’d learn from guys at school. It was fantastic.

How far did your ambitions go when it came to Quiet Sun?

At school you form bands; there were some very good musicians there, like David Rhodes, who’s played with Peter Gabriel for the last 40 or so years. And Bill MacCormick, who went on to play with Robert Wyatt in Matching Mole. We were swept up in everything – The Beatles, the Stones, The Who, The Kinks, Jimi Hendrix. Everything exploded. But, for us, it was mainly Soft Machine, because Bill knew Robert. There they’d be, rehearsing in the front room, five minutes from the school.

We were just obsessed by Soft Machine. Psychedelia was happening, the Roundhouse was happening, Soft Machine and Pink Floyd were the hippest bands in London in 1967-68. It was just revolutionary. At the same time, my brother said, “Let’s go meet this guy, he’s just turned professional.” And it was David Gilmour, the week he joined Pink Floyd. After lunch, we went back to his flat – Syd Barrett lived in the same building. David picked up his guitar and went off to Abbey Road to start recording A Saucerful Of Secrets.

Nico whispered: ‘Ignore everything John Cale says, just do whatever you want to do. Don’t bother with that person up there’

And I remember going to Ronnie Scott’s with Robert and Bill to see Charlie Mingus. I suppose that all influenced the kind of music that Quiet Sun made, so we just did our version of that, which eventually became an album [1975’s Mainstream]. Next year is the 50th anniversary and we’re going to be doing a special edition with the four of us writing and recording a new song each.

You’d just turned 21 when you went for your second audition with Roxy Music in early 1972. What made you think you’d be a good fit?

I’d listened to so many different kinds of music and I understood prog, or whatever it was called then. I understood complicated music, I understood systems music, and then experimental music and free-form. I wasn’t afraid to fail; I had the chops from having done the equivalent of prog rock in Quiet Sun – songs in 17/8 and 7/8 and 5/4; really tricky stuff. And then meeting the Roxy guys and auditioning on a two-chord number, I sort of stepped up.

I’d gone to another audition for somebody and failed, then I failed the first Roxy audition. I thought it was never going to happen; but, musically, I felt confident. Roxy were arty types and we all loved The Velvet Underground, so I knew what to do in that musical context. And it wasn’t jazz. I didn’t want those kinds of chops – I wanted ambient-type sonic textures. Roxy seemed to combine so many things. They were different and I could tell they were special. I was looking at these guys and thinking, “Wow, this is my dream!”

It also led to a fruitful relationship with Brian Eno, which has continued over the years.

We got on incredibly well. In between the first and second auditions for Roxy, we were both at Steve Reich’s concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and we bumped into each other afterwards. We generally had lots of musical references that weren’t necessarily to do with being in a band. Eno was a sort of kindred spirit, musically.

In 1974, you and Eno both appeared on Nico’s The End…. How was that experience?

Like most people around, I was a total fanboy. I had the original Velvet Underground albums, then the solo albums, that whole world of hers. So she was this goddess-type person – just to meet her was fantastic. Her relationship with [producer] John Cale was hilarious. The playing area at Sound Techniques is down some steps, a bit like Abbey Road’s Studio Two. Nico came down and just whispered: “Ignore everything he says, just do whatever you want to do. Don’t bother with that person up there.” So I just did my thing on The End, which was a favourite Doors track. She gave it the super-spooky death chill.

You released your first album, Diamond Head, in 1975. Did the solo career and Roxy feed off one another?

Not really. We all realised that we had a lot of music in us that wouldn’t necessarily fit into the Roxy band concept. It was a case of ‘save it for your solo record.’ Everyone had already done solo albums, so I put my hand up and said, “Can I do one?” And they said, “OK, off you go.” I thought, “Right, I’ll ring up all my mates who’ve got nothing to do with Roxy.” That’s what made me embark on these albums. I had no intention of pursuing a solo career – it was just an outlet for all this other music that was in my head.

I thought, ‘I can’t ask someone else to sing them. I’m going to have to bite the bullet.’ It made me appreciate singers a lot more

It may be your name over the door, but your solo work has always really been a very collaborative effort…

It goes to the heart of why I became a musician: because I wanted to meet people, have musical conversations with them and be free. The label weren’t really interested; they were more interested in Roxy and making money. So I could just do whatever I wanted with whoever I wanted. Diamond Head was done at Basing Street Studios [originally Island Studios] with all the guys from Roxy, plus John Wetton and Robert Wyatt and Eno. It was just great fun.

You’ve never been a showboating guitarist. Was it always about creating atmospheres for you, approximating the sound of influences like Mike Ratledge, Miles Davis or Charles Mingus?

That’s my voice, if you like. I used to joke that I made a whole career out of it, because my sense of tuning is different. That’s why, eventually, I did an album called Primitive Guitars [1982], because I consider myself a sort of primitive guitarist. I didn’t want to have incredible technique. I decided, when I was 18, I’d go down a different path. But one thing I really did like: I wanted my guitar to sound like the first Lowrey organ of Mike Ratledge – that distorted sound with echo. But the person who actually achieved that was Robert Fripp!

What was the idea behind forming 801?

It was like an Eno art project. The MacCormick brothers [Bill and brother Ian, aka music journalist and writer Ian MacDonald] were involved. We went to this cottage, the four of us, and hatched this idea. Funnily enough, I’ve got some Super 8 footage of us there, sort of mucking about. That was only designed to exist for six weeks, musicians and non-musicians pitted against each other. We used material from our solo stuff and a couple of covers. We planned to do gigs; in the end we did three.

In Conversation With Andy Mackay – YouTube

We recorded one of them and that’s what you hear on 801 Live [1976]. It’s the best solo project I’ve ever been involved with. In 2026, we’ll be releasing a box set to celebrate 50 years of that. We’re already starting to work on it and we’ve got some stuff that people haven’t heard before.

These anniversaries are piling up, aren’t they?

They are, because the clock’s ticking! Who knows how long we’ve got to do this stuff? Actually, there’s a queue – there’s so much Roxy stuff to collate. Tracks from Avalon that no one’s heard; stuff like that. Lots of digging and delving. They’re not big projects, although the Avalon one will be. The For Your Pleasure box set hasn’t even come out yet.

You say you had so much music in you, but the lyrical and vocal aspect of your solo career didn’t really come to the fore until 1999’s Vozero. How come?

In 1999, I started doing what I call the three white albums, because they’ve got white covers: Vozero, 6PM [2004] and 50 Minutes Later [2005]. I started looking inside and writing songs with lyrics. They’re absolutely personal songs – there’s around 30 songs across these three albums – and I thought, “I can’t ask someone else to sing them. I’m going to have to bite the bullet and do it myself.” It also made me appreciate singers a lot more: the different kinds of interpretation that you can do at a microphone, your psychological headspace.

In Conversation With Andy Mackay was a crazy sort of idea: just ring Andy!

Were you just at a point in your life where you’d started to look back?

Yeah, those albums totally reflect my life position from those five or six years. I’d got divorced, I’d remarried, I was living in a different place. I was looking backwards, looking forwards. But the people who joined me on my different adventure were my closest bunch: David Gilmour, Bill MacCormick, Robert Wyatt, Andy Mackay, Paul Thompson, Eno doing treatments on guitar.

The Sound Of Blue [2015] feels like a dry run for your written memoir. There’s a travelogue element to it as well.

Yeah – that’s why there’s stuff like 1960 Caracas, because I lived there as a kid. Magdalena, the first track, is named after my mum. The Sound Of Blue itself was really to do with thinking about Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, not in the literal style of music. So all these different references were in there. Halmstad was where I did a prog rock orchestra thing in Sweden. Tramuntana is in Mallorca, near Deià, which brings back memories. In Conversation With Andy Mackay was a crazy sort of idea: just ring Andy! And then [Jay-Z and Kanye ‘Ye’ West’s] No Church In The Wild [which samples Manzanera’s K-Scope] had just come out and I wanted to do my own version.

Did you discover things about yourself through the process of preparing and writing Revolución To Roxy?

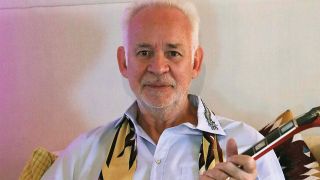

I realised that I was trying to make sense of my musical career over 50 years, and also my family’s background. En route, we started discovering all this stuff that we had no idea about. And it’s still going on, though I haven’t been able to put it in the book. I know it sounds like a joke musical or something, but one of my ancestors was a famous pirate in the Caribbean. We found a picture of him and he looks a bit like I did when I was 21 in Roxy, with long hair and boots. So, it’s been a way of making sense of Roxy, my solo stuff and why I’ve worked with so many different people.

When I was compiling this box set, I looked through and found some rare stuff. Disc 11 [The Manzanera Archives: Rare Two] is really an encapsulation of why I do this solo stuff. The first track is with this amazing griot kora player from Guinea, N’Faly Kouyaté, mixed with my guitar. There’s my demo for the Pink Floyd track, One Slip, that I gave to David Gilmour [for 1987’s A Momentary Lapse Of Reason], South American things, a live track from Ronnie Scott’s, all kinds of stuff.

The improvised The Unknown Zone, recorded with Eno and Robert Wyatt, is on there, too. It seems to be a perfect summation of that aesthetic.

It is. And it’s nice to be able to put all this stuff out and then get on with the future. We’ve got this live AM/PM album, which will be out at some point. [In March], Andy Mackay and [Roxy Music drummer] Paul Thompson and I played three small gigs in Soho, a totally immersive evening in a screening room for about 75 people a night. About 90 per cent of it was improvised. I thought it might be a disaster, but people loved it. I was just totally blown away.

It brought me back to the original ad that I answered for Roxy – ‘Guitarist wanted for avant-rock group’ – because we returned to our original mission statement. AM/PM is an avant-rock group. So I am hoping we’ll be out doing more of that next year, if people are interested. They won’t be big shows – they’ll be small – but I think it’ll be really enjoyable.

You’ve got a lot going on for the next couple of years: AM/PM, Quiet Sun, 801, Roxy box sets…

Music is just continuous. That’s what’s great about all the people in Roxy, if you like: we’re all recording and bringing out music. I know Bryan’s working on stuff, there’s me and Andy with Paul, and of course Eno is doing his thing. I’m very proud to be part of that. I suppose you could call us the seniors of the art project that was Roxy, which I thought was going to be just a normal band. But actually, they had other ideas.

In Conversation With Andy Mackay – YouTube