On March 18, 2025, the day Mike Campbell’s memoir Heartbreaker came out, he posted the opening sentence of the book on his Instagram account: “You don’t know about me without having heard a band by the name of Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers.”

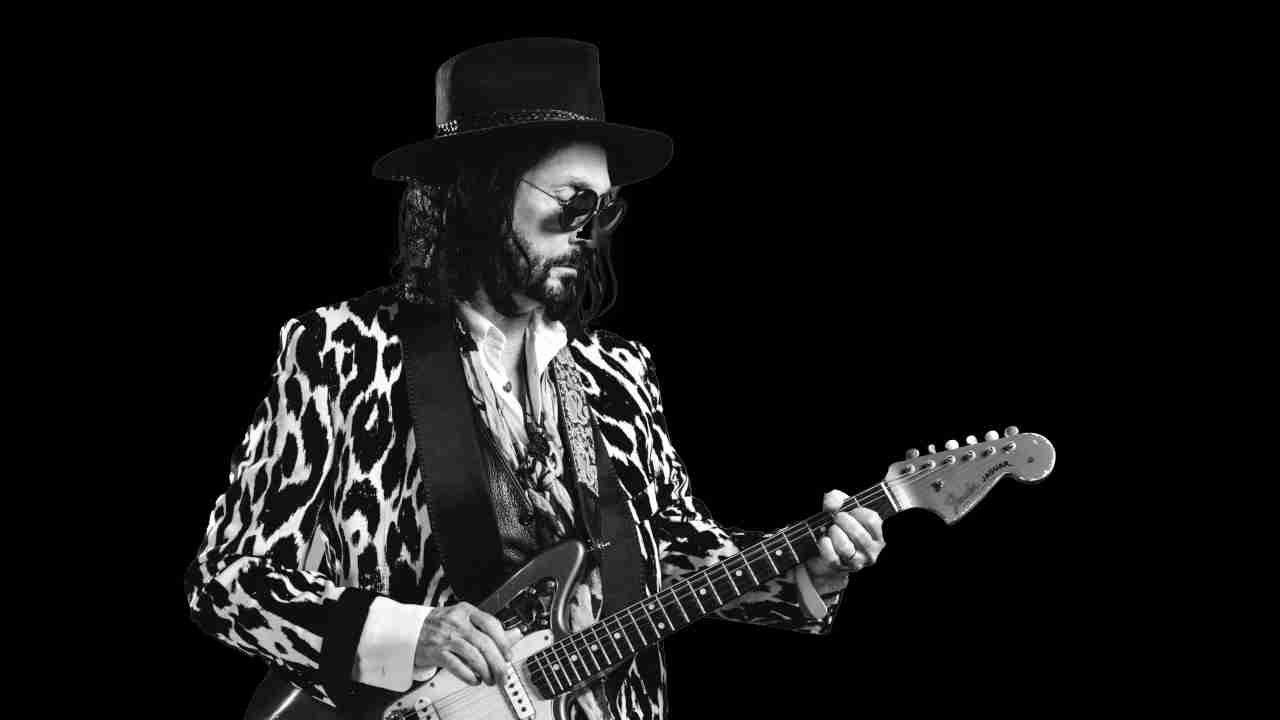

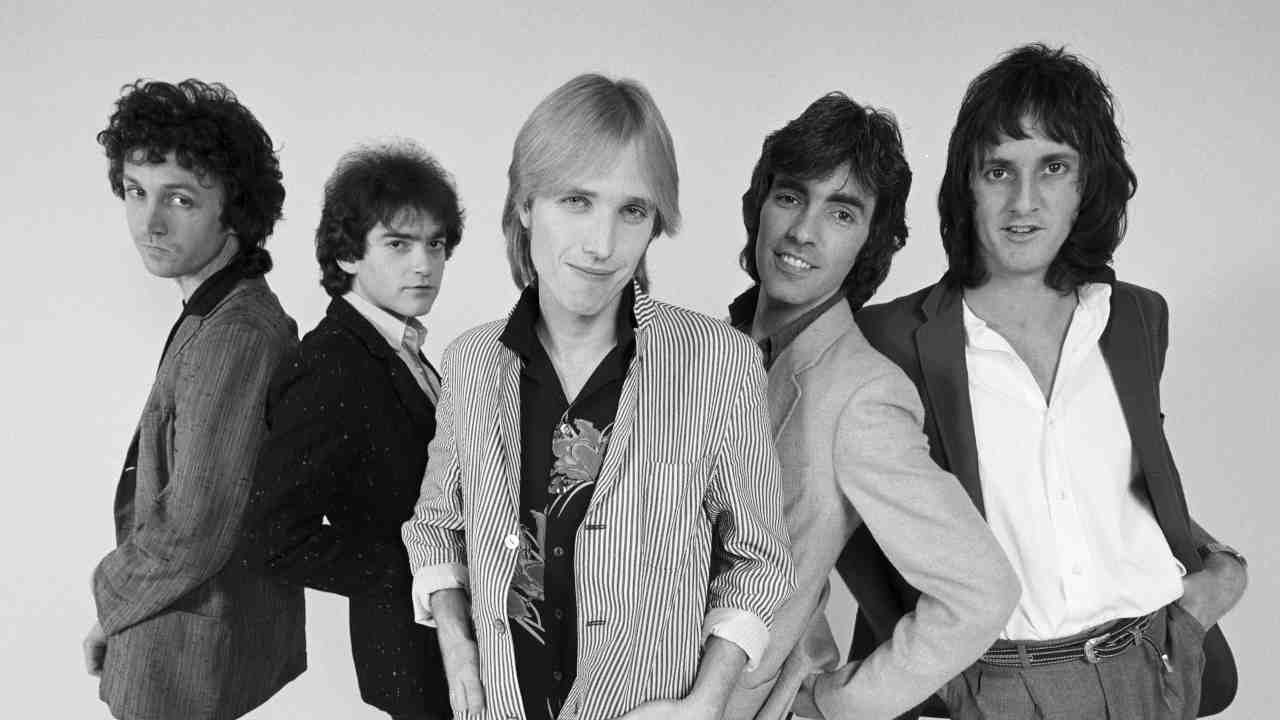

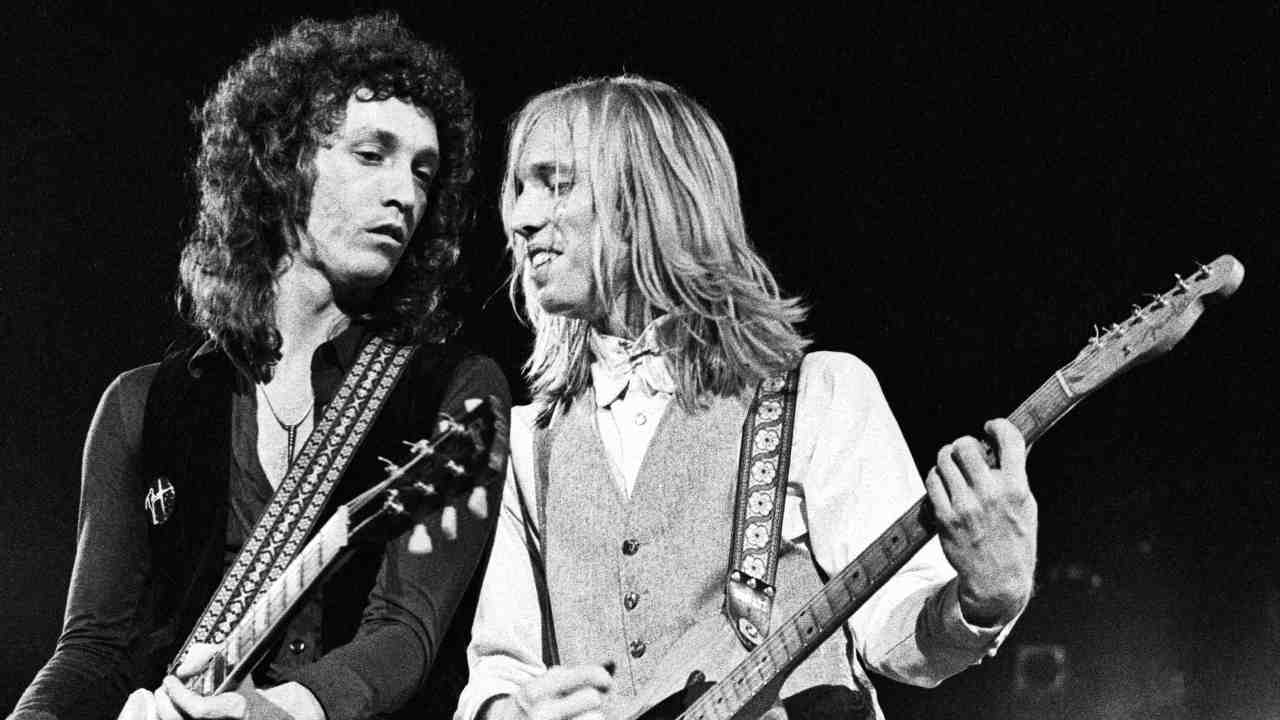

And he’s right. But that’s about to change. Up until the publication of his book (written with novelist Ari ‘Double Nickels’ Surdoval), probably everything you knew about Campbell was contained in the sound of those 13 albums by the Heartbreakers – the band he helped found in 1976, as lead guitarist, co-writer (writing or co-writing 36 songs in the Heartbreakers’ mighty canon) and co-captain, as he often likes to describe himself. But perhaps a more accurate term is liege lord: the only Heartbreaker to appear on all three of Petty’s solo albums, he was the singer’s right-hand man, apologist and sometimes dragon-slayer. He stood to the left of Petty on stage for four decades, dark, quiet, watchful, cool and a little dangerous-looking, an inscrutable contrast to Petty’s rangy, tow-headed, insider deportment and brutal confidence.

While they were markedly different in temperament, demeanour and core competency, what bounded the two were a shared a British Invasion sensibility in the music they loved – not common among their Northern Florida brethren – and dreaming the same dream, a dream they could only achieve together. Although if cornered, both would have been loath to admit it.

“Tom never doubted that we would make it,” Campbell writes in the intro to Heartbreaker. “He always knew we were going to the top. Nothing was going to stop him. He was little and he was skinny, but he could be unbreakable. He could withstand pressure like nobody I have ever seen. Tom Petty was one of the toughest people I have ever met, but it could make him hard on people.”

Including Campbell.

Petty was always seen as the ‘people’s rock star’, the link between the common man and the rock stars up on Valhalla, like his bandmates in the Travelin’ Wilburys. Campbell paints a more complicated picture of his friend and bandmate, breaking the code of band silence about what it was like to work with the driven, often volatile, frontman.

From their first days in Mudcrutch, a swampy psychedelic rock’n’roll band they formed on a rundown farm outside Gainesville, Florida, in 1970, Campbell was at Petty’s side. He was at his bedside during his last moments, after he’d suffered heart failure following an accidental drug overdose a week after the Heartbreakers finished a three-night stint at the Hollywood Bowl on September 25, 2017, closing out their 40th Anniversary Tour.

“I think I’ll be grieving Tom’s death all my life,” says Campbell, in the lounge of his studio in Woodland Hills, California. It’s apparent that he still hasn’t fully accepted it, although Petty has been gone more than seven years – he still speaks of his partner in the present tense.

Among the things fans will find when reading the book is that the psychic costs of success are higher than most might imagine. Even something seemingly as mundane as naming the band is fraught with dominance and submission within the band.

It’s not only Petty that Campbell portrays in incisive, obsessive detail. He provides a sitcom-worthy profile of bandmate Stan Lynch, and the indignities and near-psychological warfare the drummer suffered at the hands of producer Jimmy Iovine and engineer Shelly Yakus while they were recording 1979’s Damn The Torpedoes. He recalls the kindness and humanity of blues-grouch Al Kooper, who brings bandmate Benmont Tench a turkey sandwich when he was in rehab, showing a much different side of the Super Session organist/organiser. There’s a hilarious yet edifying exchange with Gene Simmons, when the Heartbreakers opened for Kiss, in which the bassist explains the difference between primary, secondary and tertiary markets and which days of the week you should play each, as if delivering a lecture from the mount. There are bon mots about George Harrison (who asks him if he dyes his hair!), John Lydon, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash (his father’s favourite artist), and a chance meeting with destiny, a dog, and the woman who would become his wife of 50 years.

At the centre of the book, despite all the machinations, power struggles, betrayals, unexpected quirks of character and shifts of loyalties, the brushes with drugs and the death of a bandmember, Heartbreaker is not a tale of ruthless ambition and treachery, or even a tell-all, but one of endurance and transformation, and a man’s love story for a band, a woman and an era.

What motivated you to write Heartbreaker? What story did you feel that you needed telling, and why right now?

Well, to be honest, I didn’t think I needed to tell any of the stories and I wasn’t intending to write a book at all. It never even crossed my mind until my friend Jaan Uhelszki said she knew an author that was keen to write a book about me, Ari Surdoval, who turned out to be a great partner. So it came into my lap without me looking for it. I just dug into my memory banks and talked for hours and hours.

Were there things you didn’t get to say to Tom that you wished you had?

Truthfully, I had no burning desire to say anything to Tom that I never said to him when he was alive. I did sit with him at his [hospital] bedside, and I know he could hear me. He couldn’t talk, but I told him all the things I say in the book.

Your portrayal of Tom is of someone more complex and complicated than his public persona. Was it difficult for you to show his ruthlessness?

Ruthless? Really? I told the truth. I didn’t feel I had to show Tom’s hard side any more than his sweet side. His hard side, compared to a lot of people, was not that hard. He was driven and ambitious, but ‘ruthless’ sounds a bit harsh. Maybe it was domineering and controlling and powerful, but ‘ruthless’ sounds like there’s some kind of evil intent underneath it. There never was with him.

You talk about Tom’s “unbreakable” confidence. Was that contagious for the rest of the band?

Well I wish I’d have had some of his confidence. I was insecure and unsure about things. Thank god I had a partner who had those characteristics. Did it rub off on the rest of us? Yeah, it did. He was a leader. He was like the coach: “Okay, we’re going to win the game.”

You write: “Sometimes he made me so angry I couldn’t look at him, but nothing could ever split us up. Early on we made some unspoken deal that we’re going down the line together no matter what.” Did you know immediately, and was the connection just about the music?

It was immediate. It was the same when I met my wife. I immediately knew that there’s a connection here and this is going to be a long-term relationship. With Tom it was mostly the music, but I also just liked the dude. He’s fun to hang with, he was funny, he was smart, he respected my opinions and my intellect, whatever I had of it, we had great discussions about music, and we were just friends.

Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers – American Girl (Live) – YouTube

At the heart of the book, for me, are two love stories: number one for your band – you go to any lengths to preserve it – the other one is meeting your future wife, Marcie, in 1974.

Yes. The most beautiful thing about our relationship is when Marcie met me I was nobody. When we first met, she didn’t know if I was worth a shit or not. But we connected without all that shrapnel around us. It was just, you’re a sweet little kid who’s lost; I’m lost too. I like you for who you are, the little boy in there, not the rock star. No one else could ever give me that. Very few rock marriages survive, and probably most of it’s because the connection is about the star or the lifestyle and not about the little boy inside.

You were in your band for forty-one years. You’ve been married for almost fifty years. Do you think, being a child of divorce, you would go to any lengths to keep things together?

It’s my theory, it’s the best I can come up with. Maybe the emotional tumultuous moment was when my parents split up. I didn’t like that feeling, and so going forward in my life I didn’t want to have things break up.

You talk about your insecurity and doubt, but what was the moment where you started to believe in your talent?

I don’t remember the specific situation, but as a rule the better I got on the guitar, the more girls would talk to me. And then of course when I met Tom he was very supportive. That gave me confidence. [Producer] Denny Cordell was a heroic figure for me. I never thought I could write until he told me I could. Rick Rubin did that too. He recognised something in me. There’s been lots of times along the way. George Harrison was so kind to me and complimented me. Dylan. And those little moments give you confidence along the way. Because musicians, most of them that are any good, are probably insecure. I still have trouble playing demos for Marcie. It’s a tortured-artist effect. It’s hard to play music that you’ve written for someone. It’s like being overly transparent and naked.

It’s funny that the rest of us think you artists live on Mount Olympus without a care in the world.

I think a lot of fans don’t realise what mental and physical sacrifice and hard work goes into keeping a band together and becoming successful. Sleeping on mattresses for years, eating bologna sandwiches, driving around in Econoline vans in the snow and getting a flat tyre. They think you just walk into the studio, go la-di-dah, there’s a hit single, and off we go.

You talk about Tom separating himself from the band – having his own bus, his own dressing room – and you said he was like Elvis. What was the clearest indication of that change? Did you feel the connection between him and the band was getting more tenuous?

It was not a big moment when he got his own bus, but until then the band was always in the van, always in the same bus, always around each other, for years. For Tom, I thought he’s probably sick of us. We’re probably sick of him. We’d talked about everything there is to talk about, and we probably need some space. It wasn’t a big deal, but there was a line drawn.

But that wasn’t the end of it. When Elliot Roberts came in as part of the management team, he called a meeting and informed the band – Tom wasn’t there – that going forward, Tom would receive fifty per cent of the profits and you, Benmont Tench, Stan Lynch and Ron Blair would split the other half among the four of you.

Everybody wants to talk about that!

Since you put it in the book, you have to talk about it. You convinced the rest of the band that it was better to stay than quit the band. Why weren’t you resentful?

Well, first of all I really like Elliot. He was always stoned and making jokes and maybe bent the truth now and then to tell you what you wanted to hear. Even if he was being hardass, people liked him anyway.

The band meeting was awkward and I didn’t have time to prepare for it. The new split wasn’t like we were going to talk about it, it was this has already been decided and take it or leave it. My first reaction was like when Tom got his own bus: we’ve always done everything together. It’s always been five for one and one for all. Now it’s not.

Then he laid it out for us: this guy’s doing this, this, this, this, this, this, this. They shouldn’t get as much money as this guy who’s doing all the shit. Meaning Tom. I completely got that. And like I said in the book, I figured, well, why bellyache over this? It’s logical, and if I was Tom I’d probably be saying the same thing. If we don’t get hung up on this issue we can all do well. Which we did. At that point we hadn’t seen the money yet, but we could feel that we were going to be successful. We were already playing bigger places and the records were selling more. So I thought, just sit back and enjoy the ride, don’t get hung up on greed. I think some of the other guys got a little more threatened and emotional about it. I saw that, and I said: “Try to look at it my way.” They finally got it and everybody calmed down.

Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers – Refugee – YouTube

Did you feel similarly when you asked him for a raise? When you made Damn The Torpedoes you were contributing more than just playing guitar: co-writing Refugee and Here Comes My Girl, doing a lot of arrangements, coming up with a lot of the hooks and putting finishing touches on the tracks. You told him: “I was thinking maybe I could get a little bit more of the pie on this one, because I was such a bigger part of it.” And he just stared at you and said: “Yeah, but I’m Tom Petty.”

It was even more comical, because I kinda knew he was going to outfox me, because he always did. But the truth is, after that conversation he did turn around and give me production points on the sly; the band didn’t know about it. So the outcome of that conversation of “I’m Tom Petty” was he went home and thought about it. “Mike’s probably got a point. I’ll give him a point.” On [1989 solo album] Full Moon Fever he gave me a huge chunk.

When he said that it was like I can’t really argue with that. Checkmate. Like: “Yeah, but I’m Mike Campbell.” He would be like: “Well nobody knows who that is.” You got me there. You couldn’t pull the wool over his eyes, and he would draw his line and he would convince you that that’s where the line had to be.

Can we talk a little about working with Jeff Lynne, who did production on Full Moon Fever? He asked you if you had anything to contribute, and you said you didn’t. You said it was a wake-up call for you. What did you mean by that?

First of all, it was inspiring and exciting to work with Jeff. When he came in the room, you really did want to try harder. But the thing I learned was that you had to come with your best stuff, or he’d do something better.

I always felt he was gently pushing me to be the best I could be, and he always seemed to get excited when I would do something good, which would inspire me more. Jeff has this thing – he’s really dead-on with pitch, especially with singing. He can tell if it’s a little sharp or flat. Tom and I used to laugh, because if it was a little off, he’d peer over his glasses and give us this glare. We finally said to him: “Look, Jeff, whatever you do, just don’t give us the eye.”

You were asked to play guitar on the Traveling Wilburys track Handle With Care.

Jeff said play something like Eric Clapton.

But you decided after you played it that George Harrison should play it instead.

Picture the vibe of the song. It’s a gentle little pop song. It gets to the middle and here comes Eric Clapton. I did my best version of trying to play in that mould, but I knew it wasn’t my best stuff. I felt really bad because Tom was really trying to involve me in the whole thing, he and Jeff. I tried to push it off to George. I wanted the heat off me, like please don’t use that guitar part. It’s not that good. And Jeff was going no, it’s great. And George is going yeah, it’s great. I had the sound up in my guitar, so I just handed it to George and he pulled out a slide… the rest is history. When you hear what George played, it’s a hundred times better than what I played.

You talk about times you spent with George Harrison where you forgot who he was. And you say: “Sometimes it seemed like he did too.” Did you feel that being an ex-Beatle was a huge burden for him?

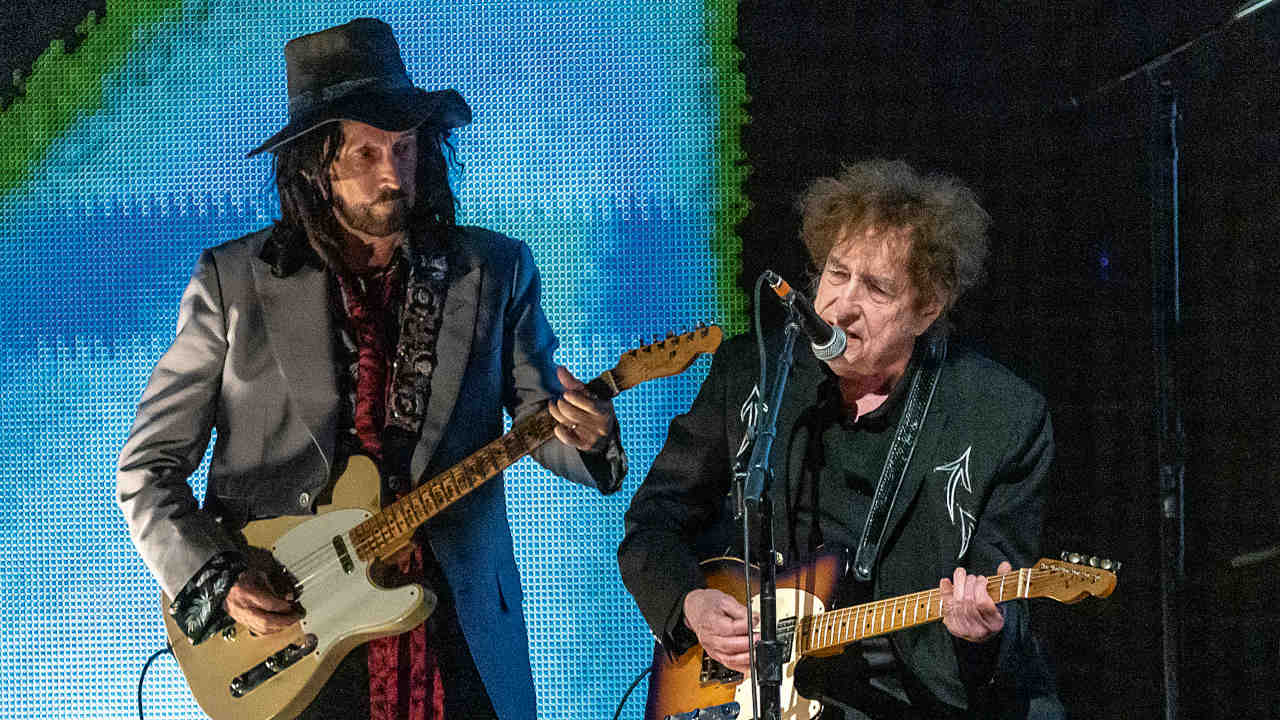

Of course it was. For all of them. But he dealt with it pretty well. I think the spirituality side of him helped him get through all that. But by the time I was hanging out with him he was not overly spiritual. He just wanted to be the musician, he wanted to be in the gang. It was the same with all those guys. When you first meet them, like Dylan or Johnny Cash, it’s like: “Oh my God, this aura is so intense.” After a while it’s like just two musicians talking about music. Bob once said to me: “I can’t talk to regular people. I don’t know what they have on their minds, but I can talk to a musician.” There’s an affinity there.

After you play your first session with Bob Dylan, he turns to you and says: “What do you think?” Quoting from the book: “The room fell silent. I froze. I gulped. Then I said: ‘It’s really long.’” Do you think he was surprised that you told him what you really thought?

I don’t think he heard the truth that much. As soon as I said it, I thought: “Oh, I just insulted him.” But he started laughing. He said: “Well gee, Mike, would you mind playing on it anyway?”

Mike Campbell & The Dirty Knobs – Wreckless Abandon (Official Music Video) – YouTube

At one point, you realise you’re writing more songs that Tom even had time to listen to, so you decided to start recording some of them yourself with a band you put together called the Dirty Knobs. You let Tom hear some of your solo stuff and he tells you: “It’s better than Keith Richards’s solo stuff, I’ll give you that.” Which at first you thought he meant as a compliment. Then he said: “What are you doing? It sounds like a bad impression of me!” It’s a particularly painful part of the book.

Well, it tapped into my insecurity. I already was afraid that I shouldn’t put it out. So when Tom said it, it didn’t surprise me that much. Plus I had expected him to have an adverse “don’t do this” reaction, because that was just his nature.

I think I even said: “Well, if it sounds like you that must sound pretty good, right?” “Yeah, but you don’t want to do that.” He asked me: “Are these songs great?” And I said: “Well, I don’t know, they’re pretty good.” “Well if they’re really great, why don’t we do them?” It’s like checkmate once again.

As I look back on it now, I’m glad I waited, because now I’m ready. I was barely learning to sing and write on my own. And so even though he was a little untactful, he was right. He did call me back the next day and go: “I’m really sorry, I was in a bad mood, but you really shouldn’t be doing this right now. We’re busy, and you don’t want to distract from the Heartbreakers.”

How were you able to move through the grief of Tom’s death?

I had no inkling he would go so early. I always wondered who would go first. We had plans to do another record and a follow-up tour to that, just keep on going. My grief was debilitating at first, and I’m still grieving. I feel his presence sometimes on stage when I do certain songs, and I’ll get a little choked up. It’s been over seven years now, so it’s a long time to still be grieving. But one way I got through the grieving process, which I learned from Al-Anon [a support group for people who have been affected by someone else’s drinking], is if you’re of service to somebody else and their issues and their dramas, that’s the best healing for you too. So I tried to do that in any way I could.

On your birthday, February 1, in 2018, Mick Fleetwood called you and asked how you would feel about joining Fleetwood Mac, to replace Lindsay Buckingham. Did that assuage any of the fresh grief? Tom had just been gone four months.

Yeah, it gave me something else to focus my mind on. I thought I was going to join the band, we were going to make a record, and then I realised, oh, they just want me for the tour. Which is fine. It was the greatest tour ever! Marcie went too, and it was like a paid vacation around the world. They treated us like royalty. The gigs were great. I enjoyed playing those songs. It was like a gift to me.

Didn’t they want you to do some Heartbreakers songs too?

I didn’t want to do any, but Stevie [Nicks] wanted to do Free Fallin’ and do a little tribute to Tom in the concert. Free Fallin’ is not one of my favourite songs, although a lot of people love it. Then in the rehearsal they asked me to do Oh Well, the Peter Green song, which is not much singing, it’s mostly talking. It’s a great guitar workout, and so that was my chance to get my confidence with my voice and being at the mic. That was the beginning of my genesis into the egomaniac I am now.

But it was a turning point for me. Steve Real, Stevie’s vocal coach, would come by the dressing room before the show and teach me some breathing and exercises. I still take the tape he made me and do it before every Knobs show. I got my [Dirty Knobs] record deal out of that. We were in Boston, and someone from the label came to see the show and afterwards they said: “We love the way you sound. Do you want to make a record?” So it came to me again. These blessings.

I’m definitely grateful. That’s part of why I wrote the book. Everybody gets some kind of blessings; you just have to be able to recognise the blessings when they come your way and embrace them.

I think you have actually figured out the key to happiness.

Well I’m trying. I remember once we were in Australia, and Bob Dylan did an interview with some local journalist, and the guy goes: “So listen, Bob, are you happy?” And without missing a beat he goes: “Happy? They have pills for that.” So that’s my answer.

After Tom died, you rejected the idea of the Heartbreakers continuing without him, at least under that name. Do you think over time you might change your mind?

No, we’re not like that. It’s not going to happen. That was Tom’s band, that was our band with Tom. It would feel awkward and it would feel sad. It’s like that ship sailed. And I think it’s okay, just remember it like it was.

I like doing the occasional Heartbreakers song with the Dirty Knobs every now and then, because the people know the songs and I get to sing them my own way, and I wrote it so it’s mine anyway.

There’s so many Heartbreakers tribute bands now. I check them out only out of curiosity and go: “Oooh, no, no, no”. So I don’t want to feel like one of those.

They work all the time. This one band, they have gigs booked all year long, clubs across America doing me and Tom. And the guy they get for me never looks like me. Some of them have guys that look sorta like Tom, but they always get some fat, ugly guy to play my part.

I’m using that, by the way.

That’s okay. Fuck those guys.

Heartbreaker: A Memoir by Mike Campbell is available now in hardback, eBook and Audio via Constable.