You can trust Louder Our experienced team has worked for some of the biggest brands in music. From testing headphones to reviewing albums, our experts aim to create reviews you can trust. Find out more about how we review.

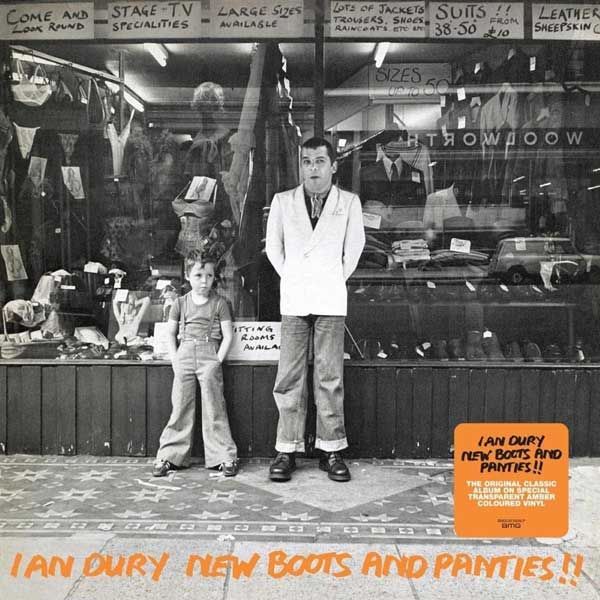

Ian Dury: New Boots And Panties!!

Wake Up And Make Love With Me

Sweet Gene Vincent

I’m Partial To Your Abracadabra

My Old Man

Billericay Dickie

Clevor Trever

If I Was With A Woman

Blockheads

Plaistow Patricia

Blackmail Man

Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll

Equal parts music-hall scamp, art school troubadour, estuary poet and new-wave figurehead, Ian Dury was many things to many people. But he was little more than a pub rock also-ran, fronting Kilburn & The High Roads, until he signed to the fledgling Stiff Records and delivered what became the label’s first gold album.

Revisiting the world of New Boots And Panties!! more than 40 years on, its 10 tracks still astonish and amuse. Dury was establishing himself as a simultaneously unlikely and obvious pop star, whose dry wit, jazz-tinged musical flights of fancy and innate sense of what makes for a rousing singalong marked him out as a true one-off. Although the album spent close to two years in the UK chart, it didn’t produce anything remotely resembling a hit single.

Even so, several tunes took on lives of their own – like Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, included as a bonus track with early repressings – to the point where younger listeners or latecomers would be surprised to learn that they either under-achieved on 45 or were never even picked out for radio play in the first place.

Sweet Gene Vincent is one of the greatest tributes to a dear departed rock star, an articulate tongue-twister that conjures images of suburban dance halls, racy women and booze-fuelled regret; Billericay Dickie is a cheekily vulgar anthem that sounds like it should be echoing out of the showers at a rugby club; My Old Man paints a loving portrait of Dury’s own bus-driver dad. All are performed with brio by The Blockheads, a ragbag ensemble with more than a hint of Disney villain about them, knocked into shape by keyboardist Chaz Jankel, co-writer of the lion’s share of the material.

As calling cards go, the album is perhaps even more fondly regarded than Stiff’s other landmark debut of ’77, Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True.

Every week, Album of the Week Club listens to and discusses the album in question, votes on how good it is, and publishes our findings, with the aim of giving people reliable reviews and the wider rock community the chance to contribute.

Other albums released in September 1977

- A Farewell to Kings – Rush

- Bad Reputation – Thin Lizzy

- Chicago XI – Chicago

- Foreign Affairs – Tom Waits

- Rough Mix – Pete Townshend and Ronnie Lane

- Talking Heads: 77 – Talking Heads

- Aja – Steely Dan

- No More Heroes – The Stranglers

- Hope – Klaatu

- Ringo the 4th – Ringo Starr

- Beauty On A Back Street – Hall & Oates

- Blank Generation – Richard Hell and the Voidoids

- The Boomtown Rats – The Boomtown Rats

- Broken Heart – The Babys

- In Color – Cheap Trick

- What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been – Grateful Dead

What they said…

Dury’s off-kilter charm and irrepressible energy make the album gel, with the disco pulse of Wake Up and Make Love with Me making perfect sense next to the gentle tribute Sweet Gene Vincent, the roaring punk of Blockheads, and the revamped music hall of Billericay Dicki” and My Old Man. Repertoire’s 1996 CD reissue adds five essential singles – Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, Razzle in My Pocket, You’re More Than Fair, England’s Glory, What a Waste” – that nearly make the disc a Dury best-of. (AllMusic)

“Lustful opener Wake Up and Make Love With Me sets out [bassist] Norman Watt-Roy and [drummer Charley Charles’ stall as the pub rock JBs; the squalid Billericay Dickie shows that TOWIE has no new light to shed on Essex ways; Clever Trevor and Plaistow Patricia (with its child-unfriendly opening gambit of “Arseholes, bastards, fucking cunts and poofs“) were down-at-heel characters straight out of an imagined modern Dickens novel.” (BBC)

“New Boots And Panties!! just is. It doesn’t matter that its original 10 tracks peter out a little, and it spawned hundreds of lacklustre imitations, it remains a truly singular album full of magic and wonder. No small thanks to its coterie of characters, real and imaginary, that Dury brought along to so capture the imagination. They were led, of course, by Gene Vincent and Billericay Dickie, and ably supported by Plaistow Patricia, Clevor Trever and Dury’s father himself, My Old Man.” (Record Collector)

What you said…

Paul Kent: New Boots and Panties!! is an album of two halves, with songs ranging from the profane to the poignant. It’s only to be expected from a man who defined the word ‘contradiction’: a man hailed as a Cockney laureate, yet was born, not hug-a-mug to the sound of Bow bells, but, in the leafy suburbia of Upminster, Essex; a man who cast himself as a street-smart rough diamond, yet counted mentor and Pop Art pioneer, Sir Peter Blake, as one of his closest friends; a man whose work betrayed low-brow sensibilities, yet was courted by the likes of Peter Greenaway and Roman Polanski; and, most pertinently in this context, a man beloved of the punk crowd despite being backed by a crack band that were more Dan than Sham!

All of which makes reviewing Dury’s work so much more challenging. The question that needs to be asked is, did he mean it or were we all being played? The only option, therefore, is to take his work at face value and, in doing so, New Boots and Panties!! reveals itself to be nothing short of fucking magnificent! Taking the profane as our starting point, Plaistow Patricia is the oil on the water, truly nasty stuff. Prostitution, addiction, madness – who knows exactly what this heroin(e) had to endure. Certain couplets provide clues: “…she got into a mess on the NHS…“, “…it runs down your arms and settles in your palms...”, “…she lost some teeth, she nearly lost the thread…“. An uncomfortable listen, it’s ‘fucking cunts and pricks’ intro should be the least of your worries.

Further selections are cut from the same cloth: Clevor Trever extols the virtue of general ignorance; If I Was With a Woman revels in its unsettlingly casual misogyny; signature shout-along Blockheads is as relevant a piece of social commentary now than it ever was; and rounding the album off is the truly terrifying race-hate-rant that is Blackmail Man – no easy answers here…no-one is innocent and we’re all fair game! It’s a blessed relief to hear the last shard of feedback fade.

But, there’s more to this album than just sneers and bile. Before reaching the hate zone, there’s much love and much to be loved: Dury deals with the physical in the morning glory story of Wake Up and Make Love With Me, gets hard on foreplay with I’m Partial To Your Abracadabra and regales us with the saucy postcard conquests of Billericay Dickie.

However, two shots of real love hit the mark hard: Sweet Gene Vincent pays tribute to Dury’s rock ‘n’ rollin’ idol – unflinching in its honesty, yet heartfelt and true, it’s pay-off line, “…when your leg still hurts and you need more shirts…“, is proof of how much Dury admired, and was inspired by, the man. My Old Man is nothing more than a string of random memories of his chauffeur father, and yet, for someone like me who has lost their dad, its simplicity is affecting in the extreme. Estranged from my own father before his death, the line “…all the while we thought about each other, all the best, dad, from your son...” breaks me every time. It’s a beautiful song.

Such strong storytelling deserves only the finest accompaniment and they don’t come much finer than The Blockheads. In Chaz Jankel, Dury found the perfect foil – a gifted composer and visionary arranger, it’s no small wonder, and quite proper, that Jankel shared a Q Songwriter award with his guv’nor, shortly before the guv’nor died. Every track is a masterclass in studied nuance and subtle underplaying. These guys don’t break sweat. Laid-back grooves, music hall knees-ups, suave jazz stylings and high-octane blow-outs are all a walk in the park, and New Boots and Panties!! is as much their record as it is Ian’s.

After nearly 50 years, this album still packs a punch. It’s still vital, visceral and contemporary as hell, both musically and lyrically. It’s one of the few remaining albums I own that gets played from start to finish, every track savoured. It remains as uncompromising a listen as ever, with bitterness running through it, but it can also lift the heart and spirit, too. An album to cherish. Was Dury playing us? Well, with an album this good bequeathed to us, he could have been the Queen of Sheba, for all I care! 10/10

Steve Pereira: Ian Dury is the British Captain Beefheart, and New Boots and Panties!! is the missing link between pub rock and punk. A clever, funny, naughty, and outrageous album full of down-to-earth and very warm observations of everyday life. Or, more precisely, the everyday life of an Essex lad.

Glenn McDonald: Ian Dury; the epitome of the great English eccentric, and the perfect example of its aesthetic. A true one-off genius in my opinion. And this is his best work.

Gary Claydon: Punk was a great enabler. It took the independent, DIY ethos fostered by the pub rock scene and ran with it, in the process ushering in a period, in the late 70s and early 80s that was arguably the most diverse, colourful, creative, interesting and downright exhilarating in UK music history. It gave a voice to all kinds of disparate characters, even curmudgeonly Essex types who couldn’t sing for shit. For Ian Dury, it meant he had finally found his audience and with it the stardom he craved.

Even during his struggles with the fast-fading Kilburn and The High Roads, Dury had become adept at surrounding himself with highly capable musicians (and crucially for him, ones who wouldn’t be trying to steal the limelight) but his best most fortuitous recruitment came in the shape of a man he apparently told to fuck off at their first meeting, Chas Jankel.

The smart, musically savvy Jankel added funky to Dury’s funny, rounding off a style that was an eclectic mix of rock’n’roll, music hall, funk, ska, pop even disco. All this plus Dury’s trademark humour and down-to-earth writing made for something unorthodox and unique. His deadpan vocals, delivered in his Essex accent ( Dury having realised quite early on that he could never make faux-American work for him) added to a style that was highly evocative of the grittier, seedier more downtrodden side of late 70s UK life.

New Boots and Panties!! was the result. Dury’s blue-collar poetry and humour breathing life into a collection of disparate, sometimes desperate, characters, often reflecting the man’s own struggles. At times profane, biting and affectionate, it’s an album that fit perfectly with the zeitgeist and propelled this marginalised, almost Dickensian figure towards mainstream success and near iconic status.

Some of the material may not have aged all that well but for the most part New Boots and Panties!! is smart, funny, at times angry at others emotional and relatable. The band are excellent, especially the formidable rhythm section of Norman Watt-Roy and Charley Charles. Elsewhere Davey Payne’s sax and some clever use of electronics add colour and Jankel’s guitar and keys help pull it all together.

Best tracks? I’m not sure, to be honest. The original 10 tracks did tail off a bit towards the end and there’s no doubt that the addition of the non-album single, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll made the album stronger. All in all, though, New Boots and Panties!! is a truly singular album, startlingly original and a real delight.

Chris Elliott: From the profound to the profane via a boatload of innuendo – what more do you need. It is a record of its time and not everything has aged so well – the general anger and frustration of the times and the casual racism of day-to-day language in the 1970’s colours the darker elements of the album – not every bit works out of context nearly 50 years down the line.

At the time the “singles” were stand-alone records not included on the albums – I discovered Ian Dury a few years later when Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick appeared and somehow got playlisted on Radio 1 before exploding into a No 1 single. Initially, my very youthful knowledge was the singles, but a few years down the line I heard (taped off a mate) the album and that was an eye-opener. Jaunty little singles to tracks like Mr Blackmail and Plaistow Patricia that were definitely not jaunty little singles but confrontational and eye-opening offerings.

It’s lyric-led. On this album the music is secondary and borrows heavily from the cadence of music hall/pub singalong with some pub rock making up the rest.

An album that jumps from the visceral anger of Mr Blackmail to seaside postcard humour via the heart-wrenching My Old Man (which in itself quietly skewers the English Class system in passing) is a thing to be treasured.

Sex & Drugs & Rock Roll is a life manifesto worth remembering. It goes far deeper than the title, although that’s not a bad place to start.

Mark Herrington: There’s a respectful reverence towards artists like Ian Dury. Authentic, forthright and credible (and, importantly, humorous). Although he wasn’t punk, he benefitted from the punk tidal wave in the UK, which encouraged those on the musical margins. I was aware of him in the 70s via his singles, but never invested my meagre savings on any of his vinyl Instead, I was more inclined towards heavy rock, darker new wave and goth as it emerged.

Listening no , I pretty much feel the same. It’s an album I can respect, but it doesn’t really light up my musical grey matter.

I like some of the tracks such as Wake Up And Make Love With Me, Sweet Gene Vincent and Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, but wouldn’t listen to the album again. His singles were pretty good – my favourites (not on this album) being Reasons to be Cheerful and Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick, but his particular style wears thin for me over 11 tracks.

Dale Munday: Absolute 100% classic album. Riding the coattails of punk, the well-seasoned Dury assembled a band of top-quality musicians, musicians adept at playing jazz, funk, rock, vaudeville – the whole gamut of musical styles – with Dury as the ringmaster.

Philip Qvist: While the humour is likely to go over some heads, I thoroughly enjoyed New Boots And Panties!!. Ian Dury’s lyrics are clever, unique and great, while he was well supported by his backing musicians – especially Chaz Jankel.

The perfect time capsule of London in the mid-1970s, it is pretty easy to see why it got rave reviews – even in the States. Best tracks are Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, Wake Up And Make Love With Me and My Old Man – but this is one album that everybody has to listen to at least once before they die.

John Davidson: A musical oddity that has stood the test of time. Dury is a poet who half sings, half speaks his absurd and often suggestive lyrics over the top of the Blockheads’ music, ranging from pub rock to knees-up with a touch of funk along the way this is not your typical classic rock. You really need to read the lyrics to appreciate the songs at their fullest. 7/10.

Andrew Johnston: I love Partial To Your Abracadabra.

Gus Schultz: I can’t speak for America, but here in Canada Ian Dury was fairly well-received thanks to Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll getting a lot of airplay. I bought this album upon release not knowing what to expect for the rest of it. I was thoroughly impressed by what I heard and played it very regularly. Some of my favourites are Billericay Dickie, Clevor Trever, My Old Man, Wake Up And Make Love With Me and of course Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll , hell I loved the whole lot.

Here in Canada we have a much closer tie to Great Britain than the US and have been blessed with shows like Monty Python, On the Buses, Doctor In The House, Coronation Street and many more. So the lingo and very English lyrics and references were not too difficult to grasp. This album was very different and unique, combining elements of punk, reggae, and rock and very interesting lyrics. I’ve always been drawn to quirky, other-side-of-the-tracks kinda stuff and this album definitely fits. Although it may not fit the definition of classic rock, it is definitely a classic album that may not be for everyone but still gets regular play in my home and car!

Mike Canoe: I’ve been fascinated with Ian Dury ever since I saw the video of Hit Me with Your Rhythm Stick on early MTV. It’s a bit cliché, but I had never seen anyone that looked or sounded like him. Of course, I was a young teen in the pre-internet 1900s so my musical experience was still pretty limited. Somewhere along the line I figured out that song wasn’t readily available on an album and filed Ian Dury in that corner of my mind where I kept artists that I liked but not enough to buy.

When YouTube became the world’s jukebox, I checked out New Boots And Panties!! and found some of it brilliant and some of it surprisingly juvenile. I listened to it a few more times after it was listed in Garry Mulholland’s Fear of Music (The 261 Greatest Albums Since Punk & Disco) and understood the humour a little better.

My favourites remain Wake Up and Make Love with Me and Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, solid contenders with Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick and I’m Partial to Your Abracadabra coming in just behind.

Character sketches like If I Was with a Woman and Billericay Dickie make more sense now that I’m in on the joke but Plaistow Patricia still just comes across as mean, probably because he’s singing at her, not as her, like he does on other songs. Musically, Plaistow Patricia, Blockheads and Blackmail Man seem written expressly to earn Dury’s punk tag.

My biggest takeaway from New Boots and Panties!! is that, just like US punk, punk rock in the UK was not a monolithic sound. Whether that was an umbrella term for a shared attitude or smart marketing to hook onto the current trend or a bit of both, I can’t say. I can say Ian Dury made it more interesting.

Greg Schwepe: During the four years I was a DJ at our college radio station, at least once a month, some song would quickly become a defacto “hit” on our little 10-watt fun factory. Someone would play a song on their show that kind of resonated with the campus. You liked it and played it on your show. Your friend liked it and played it on their show. Those people with the party in their backyard listening to our station with their big speakers sitting in the windows would call the station to request it… and so on. The funny thing is that is was usually not something new.

And believe it or not, Ian Dury’s Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll from this week’s selection New Boots and Panties!! was one of those songs. And when this album was picked I went “I 100% played something from that on my show!”

The deadpan (at times) delivery is the immediate charm of Ian Dury. And the accent! The accent! To a bunch of college kids in the Midwest US, this was something totally different that you didn’t hear on the normal FM rock station in your hometown.

Quirky, bouncy (Sweet Gene Vincent, If I Was With a Woman), and at times with a little rage (Blockheads, Blackmail Man), and all very English! If you were into Joe Jackson or Elvis Costello and someone gave you this album to borrow, chances are you liked it just as a well.

A fun album that you could put on at a party back in the day, then sing out loud with the last track, “Sex and drugs and rock’n’roll, is all my brain and body need.” Good advice. 8 out of 10 on this one for me.

Final score: 7.79 (44 votes cast, total score 343)

Join the Album Of The Week Club on Facebook to join in. The history of rock, one album at a time.

![Asia w/ Greg Lake - Sole Survivor [Unedited Version] - Live in Tokyo 1983 (Remastered) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/CzEkMAm5sgA/maxresdefault.jpg)