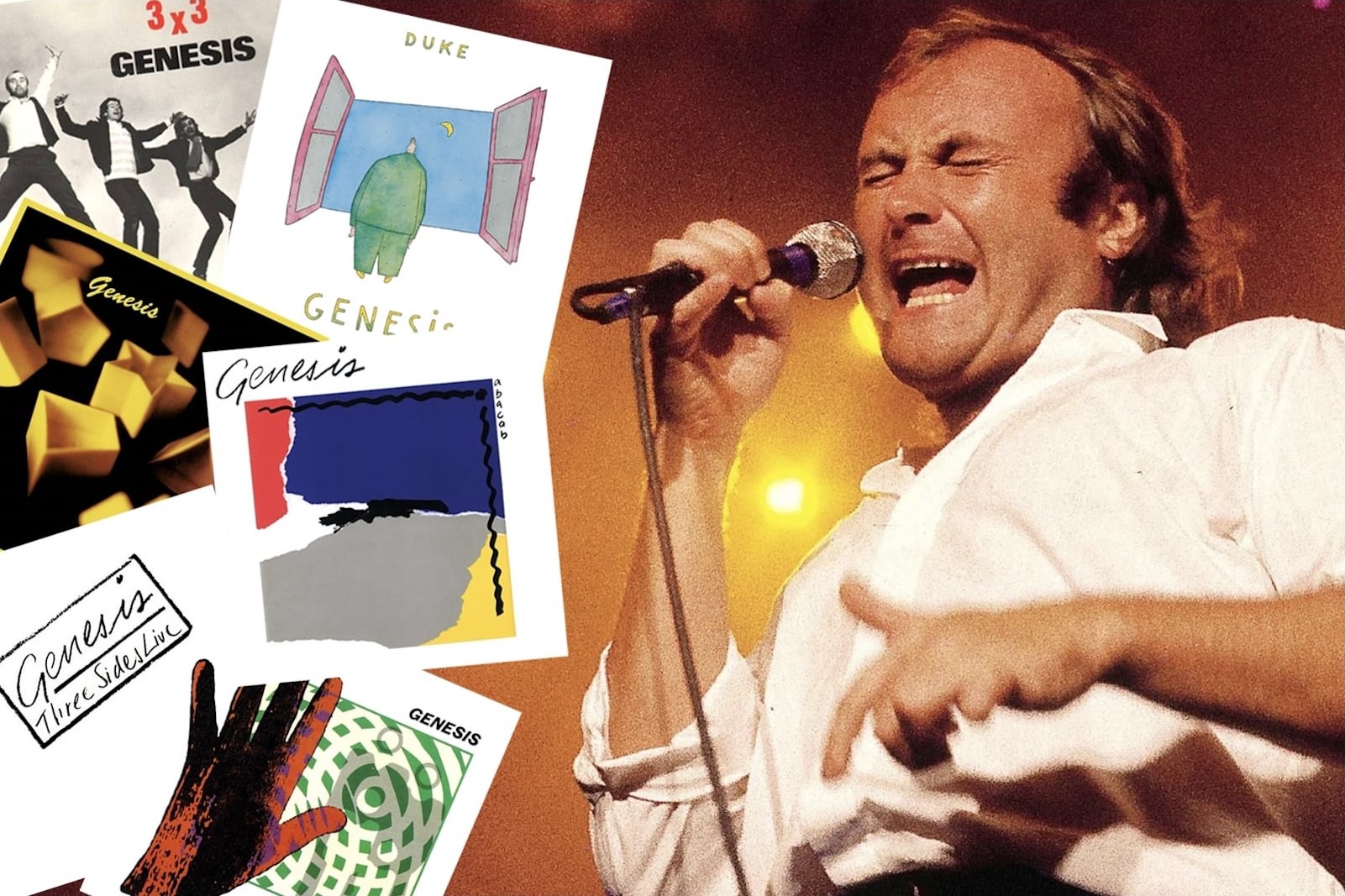

Genesis began the ’80s in transition and ended the decade on top of the pop world. Whether that was a good or bad thing might come down to your affinity for their older, more progressive approach.

Now down to the trio of Phil Collins, Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks, Genesis finished the previous decade with the transitional And Then There Were Three. The album gave only the briefest of hints at where they were headed with the U.K. Top 5 ballad “Follow You Follow Me.” Genesis made it more clear with 1980’s Duke, which included the U.S. breakthrough hit single “Misunderstanding.”

There was a brief pause in their march toward radio domination, as 1981’s Abacab delved deeply into experimentation with emerging synth technology and new-wave music. A few new studio tracks also appeared on 1982’s Three Sides Live and 3×3 EP, which had some overlapping content.

READ MORE: Next: Top 10 Phil Collins-Era Genesis Songs

These were bold steps toward a new era-specific sound – and not everyone was on board. “We decided to put a few tripwires in front of us,” Collins admitted to The New York Times, “and avoid doing some of the things we’d be expected to do.”

They kept tinkering, as Collins’ star rose. By the time Genesis issued their self-titled 1983 album and, particularly, 1986’s Invisible Touch, the group’s proggy inclinations had all but vanished. In their place were compact, polished songs that hurtled up the charts, taking the LPs with them.

Every ’80s album reached No. 1 on the U.K. charts, and after Duke, the next three Genesis LPs were multi-platinum Top 10 hits in America, too. Genesis entered the ’80s with only one Billboard Top 30 single and left with 10 – including their first-ever No. 1 with the title track from Invisible Touch. Both Rutherford and especially Collins had sizable solo hits, though again, they moved far afield of progressive rock.

The following list of Top 10 Genesis ’80s songs attempts to split the difference, acknowledging a few undeniable singles while highlighting those times when the group reanimated their ’70s-era long-form creative ambitions.

No. 10. “Behind the Lines”

From: Duke (1980)

A highlight in a not-particularly-creative era, “Behind the Lines” ultimately made promises that Duke couldn’t always keep. The track started as a fragment that linked parts to create another proggy multi-suite composition. But Genesis heard something they liked and “Behind the Lines” was built out into a proper song. Unfortunately, Duke rarely rises to this level again. Genesis ended up once again starting a decade better than they finished. The best of the ’70s era were, of course, legend-making records. On the other hand, Genesis’ early-decade successes on 1981’s Abacab and 1983’s Genesis opened the door for all of the excesses that followed.

No. 9. “Man on the Corner”

From: Abacab (1981)

With the Top 40 hit “Man on the Corner,” Genesis continued a turn toward more melancholic balladry that had begun with 1978’s “Follow You Follow Me” and continued into 1980’s “Misunderstanding.” But this one may be the most interesting, both lyrically and musically. Collins touches on his concerns for the plight of the homeless nearly a decade before taking “Another Day in Paradise” to the top of the charts as a solo artist in 1989. “Man on the Corner” also found Genesis updating their sound with a new Roland TR-808 drum machine and a pair of analog Prophet-5 synthesizers.

No. 8. “Keep It Dark”

From: Abacab (1981)

Genesis was taking bold steps toward a new era-specific sound – and perhaps nowhere more so than on “Keep It Dark.” Lyrically, this creepy tale of alien abduction still sounds of a piece with earlier Collins-led records: “The idea was that the character had to pretend that he’d just been robbed by people and that’s why he’d disappeared for a few weeks,” Banks later remembered. In fact, he’d “been to the future and gone to this fantastic world” but he didn’t think anyone would believe him. Banks then surrounded everything with a particularly canny melding of New Wave sounds. Unfortunately, we know now that he would soon be reduced to pastel pullovers and MTV-ready synth stabs. In this moment, however, Banks had tapped the zeitgeist.

No. 7. “Domino”

From: Invisible Touch (1986)

The musically layered, emotionally gripping “Domino” begins with a living nightmare already in progress: The narrator waits for the return of lover with an ever-growing sense of impending doom. Suddenly, an apocalyptic scene erupts all around, with knifing images of battle-torn drama giving unfortunate shape to his worst fears. In this way, Banks explores themes similar to the frankly tedious hit “Land of Confusion” but in a “slightly deeper manner,” Banks later told Songfacts. “It was darker, and that’s still valid.” He’d composed these lyrics while thinking of the then-ongoing Lebanon War, building toward a larger theme where a domino effect ends up taking violence from one country to another and from one heart to another.

No. 6. “Misunderstanding”

From: Duke (1980)

Banks once said “Misunderstanding” had a “California, summertime, surfer vibe” that made this impossibly hooky song “unlike anything else we’d worked on in the past.” No kidding. It makes little sense within the context of Duke, but Collins constructions like “Misunderstanding” would soon be utterly ubiquitous – both with Genesis and without. Even now, many of the hit singles are virtually indistinguishable. Frustration mounted. Genesis albums often had better deep cuts, but they still could come off like cash grabs since Collins already had a well-established solo outlet for soft-rock balladry and overproduced mechanical pop. That starts here.

No. 5. “Just a Job to Do”

From: Genesis (1983)

After engineering 1981’s Abacab, Hugh Padgham took over as producer. He quickly got to work overseeing the band’s – and Phil Collins’ – transformation into pop stars. Make no mistake, Genesis was aimed squarely at the mainstream. The album got its reboot name because of this (and also because it was the first LP to feature songs composed by all three members). “Just a Job to Do” was different, marrying nervy mechanical beats and proggy flourishes with Abacab-like deftness. The last in a trio of Rutherford compositions to open Side 2 of Genesis almost makes up for the contemptible “Illegal Alien,” which kicks things off.

No. 4. “Home by the Sea/Second Home by the Sea”

From: Genesis (1983)

The 11-minute “Home by the Sea/Second Home by the Sea” represents one of the last nods to their prog years. That starts with the theme, which amounts to a ghost story: New tenants — or, perhaps burglars? — enter a seaside dwelling, only to be greeted by spirits from beyond. These ghosts have stories. In the telling, however, the visitors become trapped inside. Banks, who wrote the lyrics, is particularly effective during the extended passage that links the two tracks. Collins had, by then, also developed into a singer of newfound range (angrily imploring everyone “sit down, sit down … sit down!“) but, more importantly, the song retains a distinctive musical character that rounds out the narrative. That’s in keeping an era then drawing to a close.

No. 3. “Turn It On Again”

From: Duke (1980)

Genesis’ transformation into a pop juggernaut began as Collins started to find his footing both as a singer and as a mainstream songwriter after the transitional And Then There Were Three. “Misunderstanding” became their breakthrough song in the U.S., reaching No. 14, but “Turn It On Again” was the bigger U.K. hit – and rightfully so. An anthemic tune that paired perfectly with the dawning of a different era, “Turn It On Again” boasts far more complexity – particularly its unusual time signature. As with “Behind the Lines,” this song started out as an interlude in the larger suite that dominates Side 2 of Duke, but was expanded into a stand-alone item once Genesis realized what they had.

No. 2. “Tonight, Tonight, Tonight

From: Invisible Touch (1986)

Invisible Touch became Genesis’ highest-charting album while reeling off hit single after hit single, including the title track, “In Too Deep,” “Land of Confusion” (which was powered along by one of the ’80s’ most memorable music videos) and “Throwing It All Away.” They’d never sounded more contemporary – and, in many cases, any softer. People tended to blame Collins but “Throwing It All Away,” one of the album’s most adult contemporary-leaning moments, features lyrics written by Rutherford. Thankfully, “Tonight Tonight Tonight” scuffed things up a bit, while still making room for these incredible atmospherics.

No. 1. “Abacab”

From: Abacab (1981)

Genesis’ best melding of new-wave and prog, “Abacab” has its feet firmly planted in both worlds. There’s no denying that punchy hook, but Genesis also exhaled for a thrilling interlude that allowed Banks a rare free-form improv turn. Sure, the lyrics are cellophane-wrapped nonsense. Weed-stoked arguments about how the title may — or may not!! — refer to its song structure likely continue. Even Collins reportedly stopped during the first verse of “Abacab” at reunion rehearsals in 2006 to say: “I don’t really want to sing this. I don’t know what it’s about.” Really, who does? Genesis simply carries us along on an utterly new-sounding exploration.

Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel Albums Ranked

They led Genesis through successive eras on the way to platinum-selling fame. Here’s what happened next.

Gallery Credit: Nick DeRiso

How We Ranked Every Genesis Song