“It’s time to restore a dynamic vision for the future that’s not just about recycling our garbage and all that”: Disillusioned by the 21st century, Jean-Michel Jarre aims to inspire a new hope

From musique concrète to stadium spectacles, Jean-Michel Jarre pioneered futuristic, yet accessible, electronica for decades. On his 2010 tour – when AI-generated art was still a theory – Prog found him paying tribute to visionary writer Arthur C Clarke, and arguing for a reboot of humanity’s future ambitions.

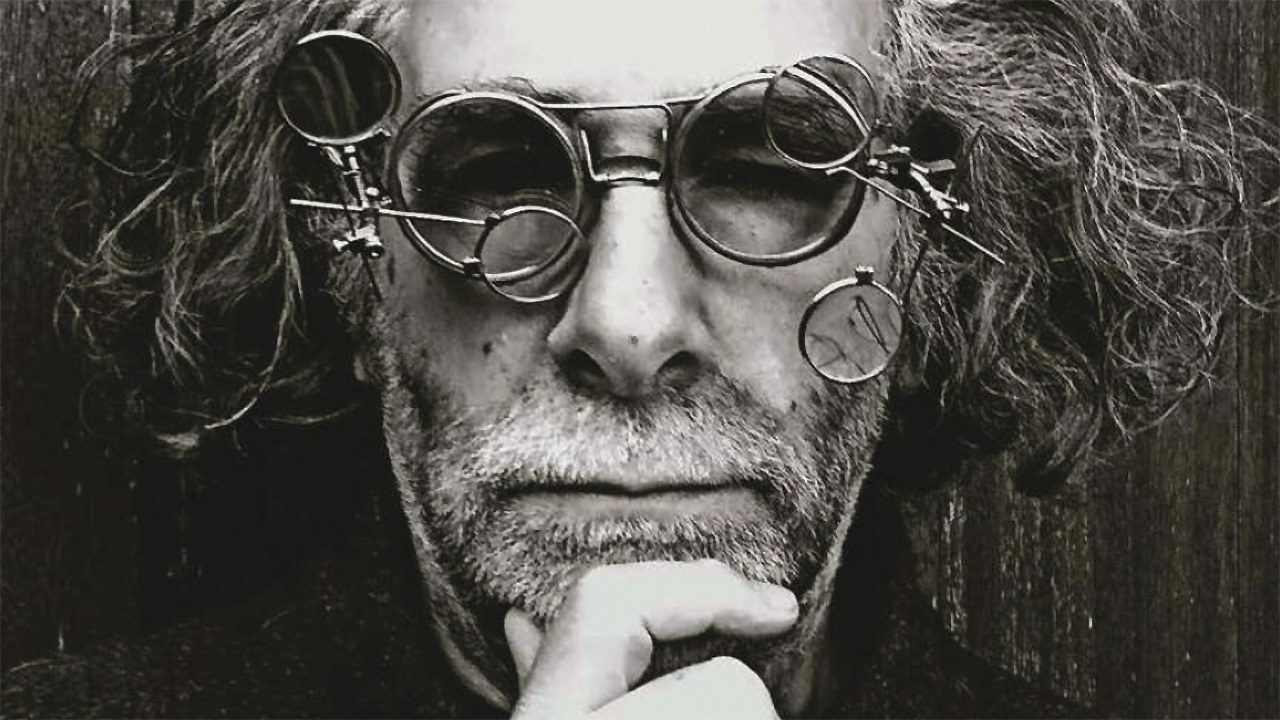

In the realm of electronic prog, no figure looms larger than Jean Michel Jarre. He’s sold 80 million albums, staged some of the most spectacular live events the world has ever seen and almost single-handedly taken the instrumental synthesizer form academia and avant-garde art centres to the masses. And yet, despite everything he’s achieved, it’s often been tempting to write him off as irrelevant.

In the wake of his meteoric rise to fame via 1977 debut Oxygène and 1978 follow-up Équinoxe, a new breed of innovators entered the electronic field. As early as 1979, former punk upstart Gary Numan started a wave of electro-pop which swept the synth stars of the 70s onto the sidelines. The cutting edge had moved, leaving meandering, album-length suites behind.

Other new such as Depeche Mode and New Order soon followed, dominating the charts while the likes of Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze and Jarre himself began to lose ground. The 1990s were even tougher, with the dominant dance music culture casting Jarre and his ilk as overblown, outdated anachronisms from a bygone age.

All this despite the enormous influence the pioneers of the 70s had on synth pop, dance, trance, techno, glitch, garage, house and just about every other form of electronic music.

Jean-Michel Jarre – Fourth Rendez-Vous – YouTube

Jarre, however, has never wavered in his commitment and his profile has remained high. He continues to record and tour regularly – and to his credit, he’s refused to play it safe. While the albums Oxygène 7-13 and Oxygène: New Master Recording have seen him exploiting the legacy that’s rightfully his, he hasn’t relied heavily on nostalgia.

Works such as 2000’s Métamorphoses – the first JMJ album to feature actual songs with lyrics – and 2007’s dance-orientated Téo & Téa have displayed a willingness to stray outside his comfort zone, take risks and even enter territory dominated by younger generations.

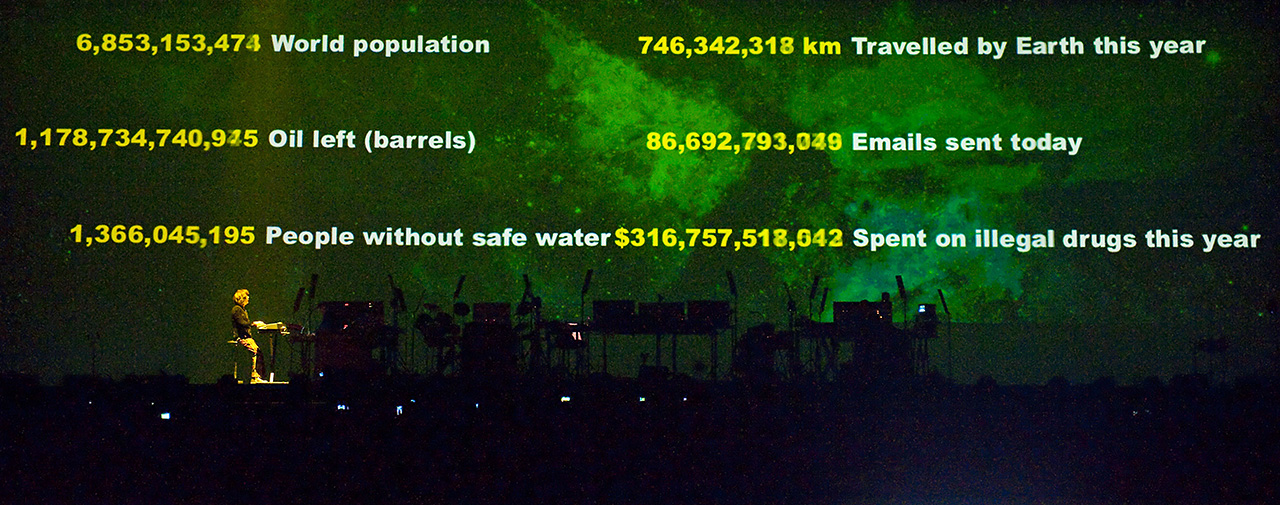

Whatever the relative merits of his studio output, his live shows have remained popular attractions, and he continues to perform on a scale few can match. Although his ongoing world tour is something of a greatest hits package, it sees Jarre innovating again and setting himself some stiff challenges along the way. Like everything he does, it’s big – but there’s an element of randomness and benign chaos in his current performances that’s very far removed from the choreographed theatrics he’s normally associated with.

“I’ve done my best to make it exciting and visual,” Jarre explains. “I’ve tried very hard to stress the cinematic side of the music for this tour. It’s not respectful to sit behind a laptop for two hours – people are buying tickets, after all. I’m up there on stage with three other guys and it’s totally live.”

What’s particularly striking about Jarre’s 2010 show is just how physical the whole thing is. Making his way to the stage through a gob-smacked audience is just the beginning. He remains animated throughout as his companions twiddle and fiddle with the vast array of vintage synths, jogging about the stage, triggering whooshing and bleeping noises as he passes each instrument, orchestrating bouts of hand-clapping as he goes.

He straps on an accordion for Chronologie 6 before firing up the legendary laser harp for Rendez-Vous. It’s as full- on as it is hands-on; and with everything happening in real time, they’re flying by the seat of their pants. “If you make a mistake on stage, people like that,” Jarre says. “It’s an element of danger. It’s a unique moment and it makes each concert different. Today so much is pre-programmed. I’m trying to make each concert as a unique moment that I can share on that evening with that audience.”

If the road trip has an unofficial theme, it’s the rediscovery of analogue. Jarre openly embraced digital synthesis and sampling when it first emerged – notably on 1981’s Magnetic Fields and 1984’s Zoolook – but time and time again he’s returned to the technology of the past and the mercurial instruments he popularised all those years ago.

The sound being played is as important as the notes being played… and there are things you just can’t do with digital

“We forgot what the analogue era gave us,” Jarre admits, “and we forgot what we owe to the period. Those instruments disappeared during the 80s and didn’t have a chance to grow up – to mature. Today, a violinist dreams about a Stradivarius, an instrument made in the 17th century. A guitar player dreams about a Gibson Les Paul ’58. For me it’s the same with analogue synthesizers.

“In the early days of digital you could play chords and notes, but with preprogrammed sounds. With analogue technology you can control the whole colour and tone of sounds. The sound being played is as important as the notes being played. People want the warmth – and there are things you just can’t do with digital.”

A perception persists that electronic music is generally cold and impersonal. In the 70s that view was rampant, and fed into wider debates about where technology was taking us. Synthesizers were perceived as inherently unmusical – even a threat to music, especially live music – and brought out latent Luddite tendencies spurred on by vague fears of the unknown.

Jean-Michel Jarre – The Time Machine Live (Laser Harp) – YouTube

“As part of my early work I was asked to do something for the theatre,” Jarre recalls, “and we had some trouble with the Musicians Union trying to unplug the speakers because they thought our machines would replace them!”

The dystopian nightmares of computer-dominated music never materialised. There has been some extremely austere and alien electronic music created over the years but the notion of technology radically undermining the basics of how music is created and performed has never come to pass. Most experiments with pure computer-generated music have proved to be dismal failures from a human perspective.

Since the 60s, when we talk about music we’re talking about songs. But music, historically, is without words

And therein lies one of the secrets of Jarre’s success: the human dimension. His tonal palette may be ethereal and otherworldly, but he himself remains the focal point and he is a star in the old fashioned sense. Where Tangerine Dream all but disappeared in darkened Gothic cathedrals, and Kraftwerk attempted to engineer themselves out of existence with robotic replacements, Jarre was centre stage, swamped by high-tech paraphernalia, lit up like a Christmas tree and with a million quid’s worth of fireworks exploding overhead.

He’s a celebrity who’s been married three times – twice to actresses – and a TV chat show regular who appears in glossy entertainment weeklies like Hello! How much do you know about Edgar Froese or Ralf Hütter’s private life?

Jean-Michel Jarre – Equinoxe, Pt. 5 (Official Music Video) – YouTube

Aside from Jarre presenting a human face, his early compositions had an organic feel which appealed to many who wouldn’t otherwise have considered themselves fans of electronic music. His warm tones, bubbling melodies and subtle French folk music influences created a welcoming, reassuring audio world, even when the mood was melancholy or reflective. Crucially, its instrumental nature meant it could go global, crossing cultural boundaries to become a truly universal language.

“What’s unique in instrumental music is that you’re in the direct narrative process,” says Jarre. “You’re giving a story to someone. Instrumental music is the most interactive way of expression, where you leave the audience free to build their own story, their own scenario or their own movie in their minds.

I always thought it was artificial to call one part Oxygene: Fool On A Hill when I’m not telling the story of a fool on a hill!

“I always felt there was something very special about music without words. Since the 60s, when we talk about music we’re talking about songs. But songs are just a sector of what is music – music, historically, is without words.

“For me, electronic music is like painting: dealing with different textures and colours to create perspectives and soundscapes rather than telling a story. The reason so many of my albums have a part one, part two, three, four, five is I always thought it was artificial to call one part Oxygene: Fool On A Hill when I’m not telling the story of a fool on a hill!”

On first hearing, his music sounded highly futuristic. The clean lines and precise pulse seemed to evoke visions of a wondrous age to come, an era of enlightenment for a united humanity. Jarre’s portrait on the rear of Equinoxe depicts him in a silvery space suit, set against a spacious, spotless cityscape at sunset. It’s an image of man, his urban environment and nature in harmony, a tantalising glimpse into a positive future for humanity set to the soundtrack contained within.

The sense of joy and wonder found in Oxygène and Èquinoxe has never been lost. Mankind may be farther than ever from the utopian future of past promise, but Jarre maintains his positive outlook.

His latest tour is dubbed 2010 for more than the obvious reason. It’s a tribute to Arthur C Clarke, the towering literary and scientific figure who’s been immensely influential in Jarre’s life and work. One might even call him a mentor. As it turned out, the feelings of admiration were mutual, with Clarke writing in his book 2010: Odyssey Two, “I listened to all of Jean Michel Jarre’s albums obsessively, to the point of knowing every note by heart. His music accompanied me as I wrote.”

Our relationship with the future is full of anxiety and guilt… it’s quite arrogant to think we have the future of the planet in our hands

Jarre says: “I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw that! I’m a fan of 2001, the book and the movie. I was in London in 1982 when the sequel 2010 came out. I got the book and was amazed to see my name in the acknowledgements. So I wrote him a letter and we started a correspondence. He was a very interesting character. So I thought that, starting this really special world tour project in 2010, it would be nice simply calling it 2010 as a tribute to him.”

The pair shared a sense of untapped, unlimited possibility for the future development of the human race. In seeking out new sonic worlds, Jarre continues his lifelong quest to reimagine what music can be, to inspire others to reach beyond their assumed limitations and pursue the impossible.

Jean-Michel Jarre – Oxygene, Pt. 4 – YouTube

“We have a dark vision of tomorrow,” he says. “Our relationship with the future is full of anxiety and guilt about pollution, the environment, global warming, how we’re going to survive on the planet and all that. Even if it’s partially true, I think it’s quite arrogant to think we have the future of the planet in our hands.

“There’s a lot of limitation in all this and it’s time to restore a dynamic vision for the future that’s not just linked to recycling our garbage and all those things. People like Arthur C Clarke gave us a very positive vision of the future. It was like after the year 2000 nothing would be the same. We had a lot of hopes and fantasies and dreams about the future.

“In these days, with the year 2000 behind us, it’s a little bit like we’re orphans of our own future. I think we need to recreate a dynamic vision for our future that we’ve lost.”